The Scent of Jasmine & the Goddess of Dance

The Scent of Jasmine & the Goddess of Dance

From great devotion comes great art

Wandering through the halls and pathways of Angkor Wat, taking in the overwhelming magnificence and minute detail of the statues, sculptures, reliefs, and friezes of this, the largest religious structure on earth; close examination demonstrates that remarkably, almost every surface is treated and carved with narrative or decorative details.

Angkor wat was designed and built in such a way so as to be in harmony with the universe, planned according to the rising sun and moon, symbolizing recurrent time sequences. The central axis aligns with the planets, connecting the structure to the cosmos so that the temple becomes a spiritual, political, cosmological, astronomical and geophysical center, a mandala -a diagram of the universe.

One begins to meditate on the other magnificent art forms and craftsmanship that must have existed in the community at this time. The costumes, the finery, jewelry, paintings, music, and of course dance. I also think about what the feasts and ceremonial banquets must have been like, how the food was prepared and presented. We can only imagine because unlike stone’s ability to resist the jungle and endure the forces of nature to last for millennia, much of the fine arts and refined culture of the Khmer empire has been lost to history.

One begins to meditate on the other magnificent art forms and craftsmanship that must have existed in the community at this time. The costumes, the finery, jewelry, paintings, music, and of course dance. I also think about what the feasts and ceremonial banquets must have been like, how the food was prepared and presented. We can only imagine because unlike stone’s ability to resist the jungle and endure the forces of nature to last for millennia, much of the fine arts and refined culture of the Khmer empire has been lost to history.

Freedom of Expression

When Cambodia gained independence from French administration in 1953, it enjoyed a brief, glorious period of optimism and cultural expression, with the royal family now in Phnom Penh the city became a celebrated center for the arts and was a time that saw the emergence of a new, modern and distinctly Khmer art scene. Yet again, much of our knowledge of this would also be lost in the ensuing Khmer Rouge genocide.

Luu Meng is Cambodia’s most celebrated chef, his mother had run a bahn chao (a thin, savoury omelette) shop on Sothearos boulevard and his grandmother had worked as a cook in the Royal Palace, before opening her own restaurant. When Luu Meng was just three years old his family were forced to flee Cambodia to a U.N.-operated refugee camp inside Thailand. Meng’s family survived the Khmer Rouge by following his grandfather’s advice to ‘stay near the water’ and followed this route out of the country. Meng’s grandfather had previously fled Mao Zedong’s regime in China, eventually settling down in Phnom Penh to raise his family.

Luu Meng is Cambodia’s most celebrated chef, his mother had run a bahn chao (a thin, savoury omelette) shop on Sothearos boulevard and his grandmother had worked as a cook in the Royal Palace, before opening her own restaurant. When Luu Meng was just three years old his family were forced to flee Cambodia to a U.N.-operated refugee camp inside Thailand. Meng’s family survived the Khmer Rouge by following his grandfather’s advice to ‘stay near the water’ and followed this route out of the country. Meng’s grandfather had previously fled Mao Zedong’s regime in China, eventually settling down in Phnom Penh to raise his family.

Eventually, Meng was able to return to his homeland, and in 1993 started working at the Sofitel Cambodiana Hotel as a trainee cook, rising to the role of sous chef in 1995. Later Meng would work as an executive chef for the Sunway Hotel and in 2001 worked for Sofitel in Siem Reap. In the mid-2000s, together with his old Sofitel colleague Arnaud Darc, Luu Meng opened “Malis”, the first Cambodian fine dining restaurant in Phnom Penh.

When Malis, (which means Jasmine in English) opened, it was not just a matter of merely opening the doors and rolling out the classic dishes. Chef Luu Meng had to rediscover and redefine a lost cuisine and restore a nation’s pride and respect in its gastronomy, its culinary reputation, and the dignity of its hospitality.

Meng became part chef, part food detective -more ‘recipe raider than tomb raider- he would travel the width and breadth of his country seeking out cooks, ingredients, recipes, and techniques; listening, sampling, learning. He would then train his team of chefs, imbuing them with more than the practical elements of a dish, also sharing the stories, legends and details about the people behind them, filling his team with pride at being able to bring these dishes back to life and share them once again.

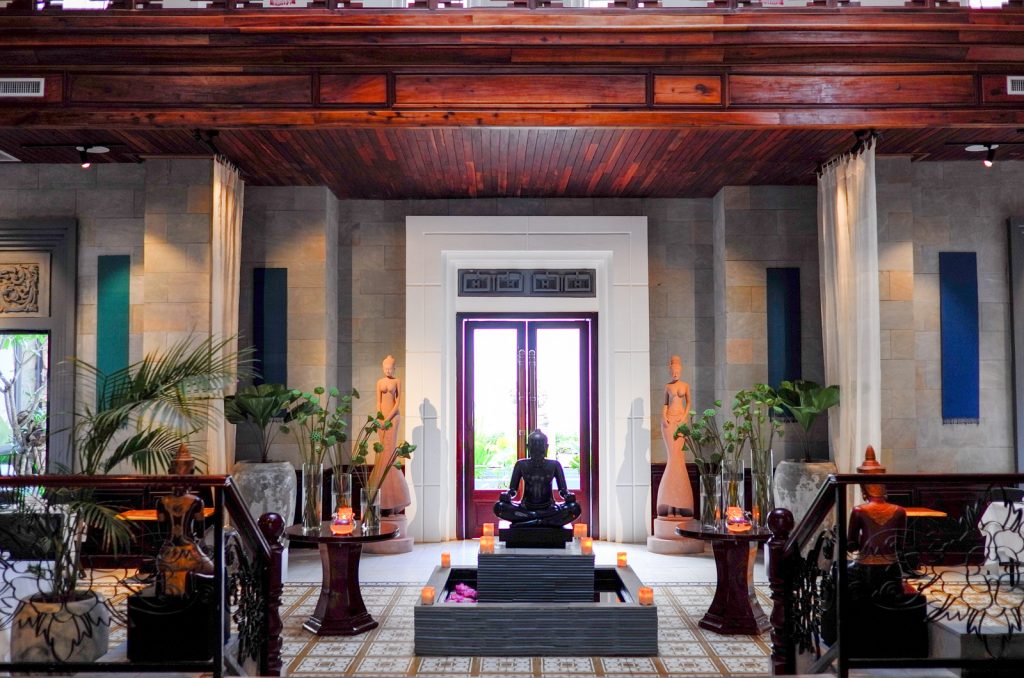

Ten successful years later, the Thalias Group opened its second Malis restaurant in Siem Reap, sharing its stunning Cambodian cuisine with the millions of foreign tourists who visit the temples each year. The magnificent new white, and silver building on the riverside is a monolithic structure inspired by the Prasat Kravan, a 10th century Angkor temple south of the Srah Srang Baray. From the outside, it has the imposing air of a palace or a state building, inside it is all food temple, a statement, and an offering of Cambodian cuisine and hospitality recreated and restored in all its glory.

Chef Meng chooses to call his cuisine ‘Living Cambodian Cuisine’ and not traditional Khmer food, he accepts that the cuisine today has been influenced by its neighbours in the region and is a cuisine that is constantly being refined, evolving, and emerging, it is a cuisine not solely of its history but also of its present and its future.

As far back as the 7th century, there is a record of Cambodian dance being performed as part of the funeral rites of Khmer Kings. Temple dancers came to be recognized as ‘apsaras’, a type of female ‘spirit of the clouds and waters’ in Hindu and Buddhist culture; they were seen as both entertainers and messengers to divinities. Ancient inscriptions describe thousands of apsara performing divine rites at temples; but when Angkor fell to the Siamese, its artisans, Brahmins, and dancers were all taken captive and removed to Ayutthaya.

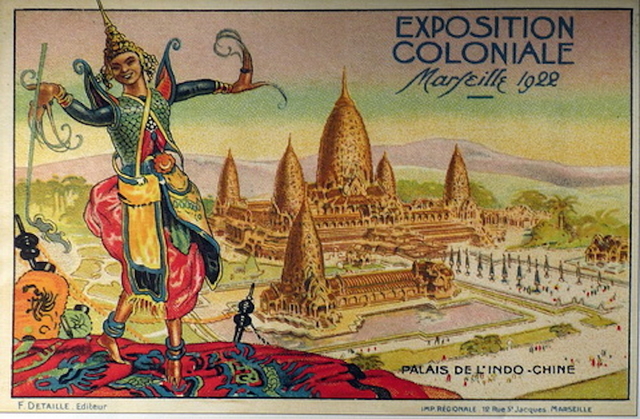

Dancers of the court of King Sisowath were exhibited at the 1906 Colonial Exposition in Marseilles, France at the suggestion of George Bois, a French representative in the Cambodian court. The artist Auguste Rodin was captivated by the dancers and painted a series of watercolors on them.

Post-independence, Cambodia’s Queen Sisowath Kossamak became a patron of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia and under her guidance, several reforms were made, including choreography, dramas were also shortened from all-night spectacles to around one hour in length. Prince Norodom Sihanouk featured dances of the royal ballet in his films.

Post-independence, Cambodia’s Queen Sisowath Kossamak became a patron of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia and under her guidance, several reforms were made, including choreography, dramas were also shortened from all-night spectacles to around one hour in length. Prince Norodom Sihanouk featured dances of the royal ballet in his films.

The Cambodian dance tradition was devastated during the terrifying reign of the Khmer Rouge; it is estimated that ninety percent of all of Cambodia’s classical artists were murdered or perished between 1975 and 1979. After their fall, those who did survive wandered out from hiding, found one another, and formed “colonies” in order to revive their sacred traditions. Khmer classical dance training was resurrected in the refugee camps in eastern Thailand by the few surviving Khmer dancers. Many dances and dance dramas were also recreated at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Cambodia. In 2003, it was inducted into the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

The Cambodian dance tradition was devastated during the terrifying reign of the Khmer Rouge; it is estimated that ninety percent of all of Cambodia’s classical artists were murdered or perished between 1975 and 1979. After their fall, those who did survive wandered out from hiding, found one another, and formed “colonies” in order to revive their sacred traditions. Khmer classical dance training was resurrected in the refugee camps in eastern Thailand by the few surviving Khmer dancers. Many dances and dance dramas were also recreated at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Cambodia. In 2003, it was inducted into the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

The Princess of Flowers

Her Royal Highness Samdech Reach Botrei Preah Ream Norodom Buppha Devi, (1943-2019) was the eldest daughter of late King Father Norodom Sihanouk. The princess spent her whole life dedicated to the performing arts. Her grandmother, Queen Sisowath Kossamak, chose that the Princess become a dancer early in her life, and at the age of 15 she became the premier dancer of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia. At the age of 18, Princess Norodom Buppha Devi was granted the title of Prima Ballerina. The young princess then toured the world as the principal dancer of the Royal Ballet with Queen Kossamak, whilst her father, Norodom Sihanouk cast her in his first feature-length film, Apsara in 1966.

Princess Buppha Devi served as Deputy Minister of Culture and Fine Arts from 1991 to 1993, she was advisor to the Royal Government in charge of Culture and Fine Arts from 1993 to 1998, she was Vice President of the Cambodian Red Cross from 1993 to 1997, and served in Prime Minister Hun Sen’s cabinet as the Minister of Culture and Fine Arts from 1998 to 2004.

As a beautiful young woman, Norodom Buppha Devi danced for the visiting Charles de Gaulle on the terrace of the ancient temple complex of Angkor Wat. The French president was said to be spellbound. Upon her passing in 2019 The Times of London noted;

As a beautiful young woman, Norodom Buppha Devi danced for the visiting Charles de Gaulle on the terrace of the ancient temple complex of Angkor Wat. The French president was said to be spellbound. Upon her passing in 2019 The Times of London noted;

“An alluring and formidable presence in and out of Cambodia through periods of turmoil and stability, the petite and delicate-looking princess, whose name in Khmer translates to Goddess of flowers always held a unique and special place in the hearts of Cambodians”.

The Princess and the Chef

Princess Buppha Devi appreciated chef Luu Meng’s contemporary Cambodian cuisine and his continuing exploration of the histories, recipes, and lore of his country’s culinaria, as well as his earnest endeavors to elevate the gastronomy and bring it onto the world stage.

Chef was asked to regularly prepare meals for her highness and she took a keen interest in Meng’s progress. It was through this that a trust and friendship developed and half a dozen years ago Princess Buppha Devi offered to share some of her favourite dishes with Meng, as a gift from the Royal Palace, these were dishes only known and prepared by the Princesses’ personal chef, who was then reaching the age of retirement. Meng of course jumped at the chance.

After several meetings and cooking collaborations between Meng, the princesses’ cook, and Princess Buppha Devi herself, Meng refined the dishes for his restaurant, and today several have made their way onto the menu at Malis.

None has become more famous and more celebrated as the Malis ‘Royal Mak Mee’, which is a cold dish that consists of crispy fried noodles topped with pan-fried sliced pork. The pork is marinated in kroeung, a traditional blend of Khmer herbs and spices ground together to form a curry paste. At Malis, the chefs grind numerous fresh ingredients including chili, turmeric, garlic, shallots, and ginger to create a robust base for many of their recipes. For the Royal Mak Mee, fragrant lemongrass is also added and the pork is slowly cooked in coconut milk.

It is fresh, clean, and divine in aroma, flavour, and texture a perfect harmony between subtle, complex spices, creaminess, and crispy noodles. A dish fit for a princess, it is an endearing and enduring culinary and cultural gift to us all.

It is fresh, clean, and divine in aroma, flavour, and texture a perfect harmony between subtle, complex spices, creaminess, and crispy noodles. A dish fit for a princess, it is an endearing and enduring culinary and cultural gift to us all.

Coda

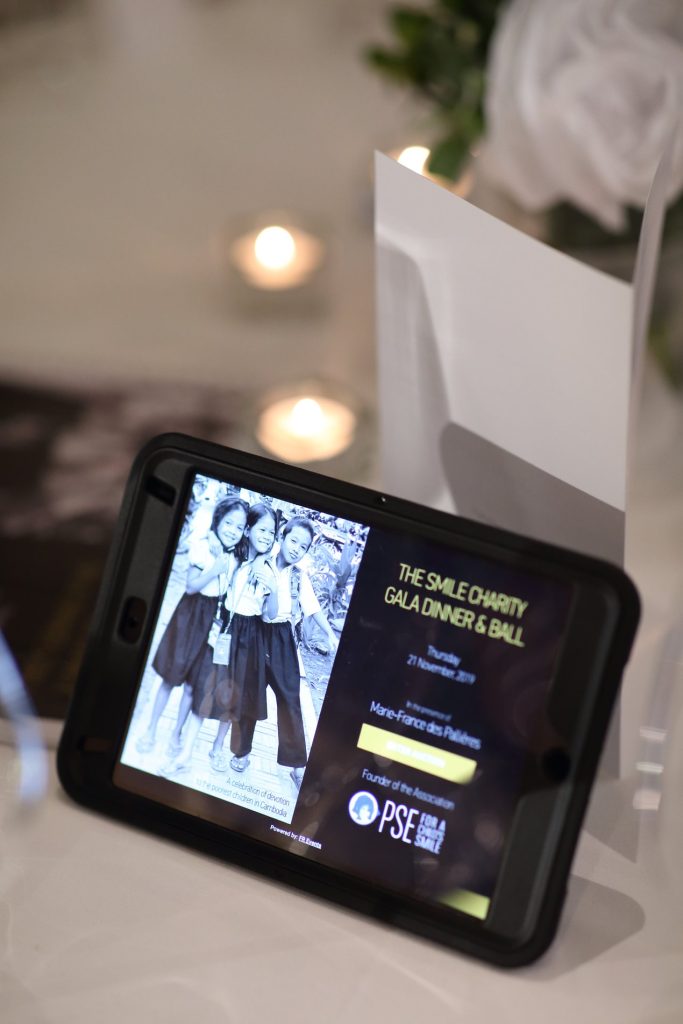

On Thursday the 21st of November 2019, I took chef Luu Meng to Hong Kong to cook at one of the oldest, most hallowed, prestigious, and most exclusive of Hong Kong’s private clubs, the LRC, which opened its kitchen’s to chef so he could prepare a special menu of Khmer dishes for a guest list of some of Hong Kong’s most refined and distinguished gourmands. This was done in order to help raise money for the Pour un Sourire d’Enfant (PSE) School in Cambodia, at an event made possible through the support of Natixis Bank Hong Kong.

The event was a sell-out, a full house; the first course was the Malis Royal Mak Mee, the audience loved it, a masterpiece in the first act, it brought the house down. This was a performance that would have no doubt brought a smile to the face of Cambodia’s great champion of Khmer culture and art, its Goddess of Flowers, Her Highness Princess Buppha Devi.