From ‘99 Boys’ to 17 Trees

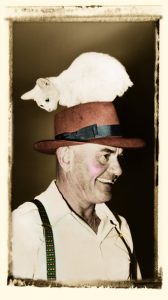

Vittorio De Bortoli hailed from Castelcucco, a small Treviso commune in the region of Veneto, Italy. The village is nestled in the Asolo Hills, under the watchful gaze of the Chiesa di San Bortolo, in the shadow of Monte Grappa. This is on the south side of the Piave River, just 17 kilometers from the famed Prosecco DOCG region of Conegliano Valdobbiadene.

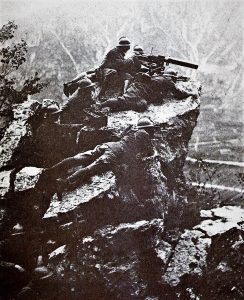

During the Great War, (WW1) Italy fought a long and debilitating stalemate with its enemies, high up in the Alpine country of the north. This commenced in 1915, with little to no gains on either side for two years. Then, on October 26th, 1917 the opposing ‘Central Powers’ launched a withering offensive; spearheaded by the Germans, they achieved a crushing victory at Caporetto. The Italian Army, under Field Marshal Luigi Cadorna was routed and would retreat more than 100 kilometers, before it would attempt to reorganize.

Ragazzi del ’99

The newly appointed Italian chief of staff, Armando Diaz, ordered that the Army stop the retreat to defend their country and save their families. Having already suffered devastating losses, the Government ordered conscription of the so-called ’99 Boys’ (Ragazzi del ’99): all males born in 1899 and prior, who were 18 years old or older.

Here at the summit of Monte Grappa, where fortified defenses had hastily been constructed, the Italians repelled the Austro-Hungarian and German Armies and by 1918, had stabilized a new front at the Piave River. Vittorio De Bortoli was 16 and the largest war that the world had ever seen, had just arrived at his doorstep. The area was the scene of fierce fighting, hand-to-hand combat; before the Italian forces prevailed at the battle of ‘Vittorio Veneto’; taking some 5,000 pieces of artillery and capturing over 350,000 enemy soldiers.

The final battle was fought from 24 October to 3 November 1918; the Italian victory marked the end of the Italian front in the Great War, secured the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and made a significant contribution to the end of the entire war itself, declared just one week later.

The ensuing years were tough times for families in the region, tough on large families with too little to go around, tough on a young, battle-scarred teenage boy, put to hard-labour on the land, barely able to scrounge enough food to eat.

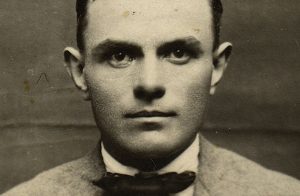

Vittorio De Bortoli arrived in Melbourne, Australia in 1924; he is said to have taken ‘the first boat out’ after the war; apparently not too fussed about its final destination. In a shell-shocked land, full of frightful memories, terrible misery and tragic loss, short of food and opportunity, anywhere else must have sounded like a chance at something better.

The young boy left his childhood sweetheart behind, promising to send for her once he had gotten himself settled. It is said Vittorio arrived, (almost a century ago) with only the clothes on his back and little to no money in his pocket. This was a journey into an Australia very different from the one we know today. In 1924, less than a third of one percent of the population identified themselves as non-British migrants, there were less than 2,000 Italians in the entire country.

In Italy, everyone made their own wine, table-wine was part of everyday life; in Australia the wine market was tiny and dominated by fortified wines, which could be transported and stored rudimentarily, without the high-risk of spoilage.

In 1925, young Vittorio made his way to Griffith, in the Murray Irrigation Area of New South Wales, hoping to find farm work. The work he found was tough, (at one point he was splitting rocks with a Spalding hammer for a living) and the pay was meagre to say the least. For a time, Vittoria lived under a water tank stand, with some hessian sacks and a few bits of tin for basic shelter. He had a knack for growing his own vegetables, which he was then able to barter for meat and other necessities. So it was, that in this way the young Italian migrant managed to get by. Before long he began to earn a living and soon enough, he was making a life for himself and plans for a family.

55 Acres

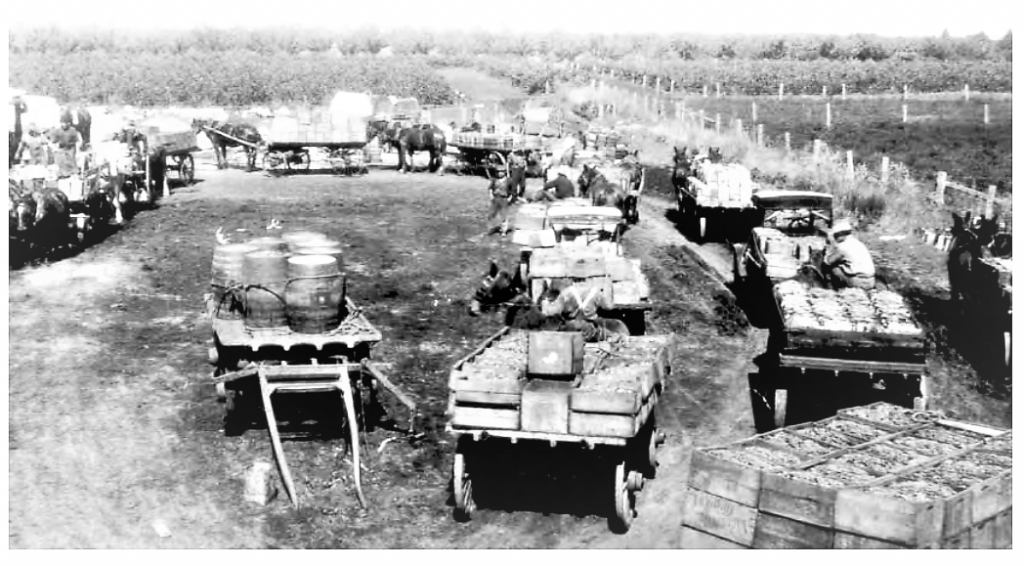

In the 1920s, returned war veterans were being allocated farmland under the soldier resettlement scheme. Many made a go of it; many others -without the skills or the capital to work their blocks- walked away in despair. Italian ‘paesanos’, working the fields began buying up this abandoned land, ‘cheap’ and it would enable them to build a future for themselves and their children.

By late 1927, Vittorio had enough money to send for his fiancé, Giuseppina Bisa, when the future Mrs Debortoli joined him they purchased a 55-acre plot of land in Bilbul, just outside of Griffith. The property was known as a ‘fruit salad’ farm back then, growing a bit of everything, including a few Shiraz grapes.

In 1928, Vittorio made some wine for family and friends, from the small plot of Shiraz grown on their farm and some grapes given to him by a few neighbours and friends. Italian migrants from Queensland and northern New South Wales, (who had been down chasing seasonal work), enjoyed the wines in the style of their home-country and convinced Vittorio to send stocks back with them up north. A wine business was born and the ‘Fruit Salad’ farm of oranges, apples, almonds, and a few grapevines, was soon fully converted over to a winegrape vineyard.

Vittorio married his Giuseppina in a simple ceremony, on their own land, surrounded by family and friends. However, these were still challenging times; the world was in the grip of the Great Depression. Despite the times, by 1931 the De Bortoli family was sending large quantities of 270 Litre barrels of wine to Queensland and Sydney -at a time when table wines were still very hard to find in Australia.

Over the next few years, the couple had three children in quick succession, son Deen and two daughters, Florrie and Eola. On the eve of the Second World War, the ragazzo di fattoria analfabeta, from Provincia di Treviso, was doing quite well at providing for his young family.

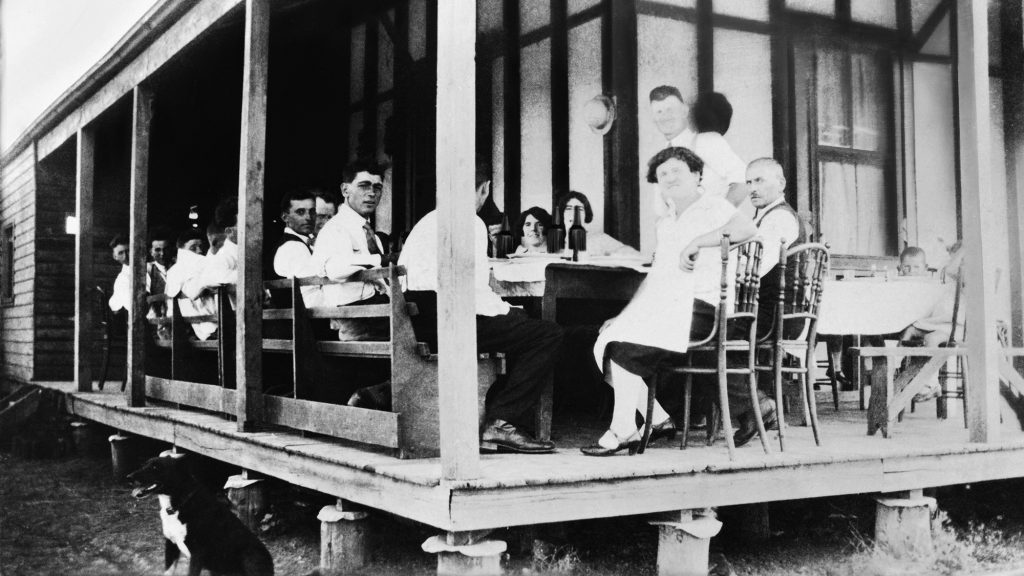

La Tavola Lunga

La Tavola Lunga, (the long table) has been an integral part of the De Bortoli family heritage ever since Vittorio put down roots in the Riverina. Vittorio was a man who loved to cook and to eat and he provided lunch every day for his family and for the farm workers who ate around a long table. La Tavola Lunga was a place to discuss business and life, and for the often homesick Italian workers, it was also a warm, hospitable reminder of home.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, the Italian migrant population in Australia suddenly found out that this time around, their mother country and their adopted country were on opposing sides. Almost 5,000 Italian migrants were locked up in Australia during the war, for simply being Italian. One can only imagine how this must have affected Vittorio with his memories of the horror of the First World War and the fighting in his commune as a young boy. This was a trauma that saw him jump on the first boat out; only to catch up with him on the other side of the world and put him on the other side of the trench.

Those interned were the males, with women, children, families left to fend for themselves. According to son Deen De Bortoli, Vittorio was apparently given a let-off as he was a significant employer in the region. However, towards the end of the war Vittorio managed to get into trouble with the government, breaking the strict new laws on production quantities and selling prices put in place for the war. Some suggest to this day he was simply doing his bit for ‘morale’ but, the government didn’t see it that way at all, Vittorio was fined and this time interned for a short spell.

15

With these skirmishes behind him, Vittorio oversaw the return to a thriving business. His son Deen joined him, working in the winery after school and during the holidays. At 15 years of age, Deen quit school -against his parent’s wishes- and demanded full-time work at the family winery. This was 1951 and in his own words his “Dad then proceeded to give me all the worst jobs in both winery and vineyard”. One recalls here that at just a year older, Deen’s father was fighting in a war that ended four Empires.

These tasks did not deter the young, aspiring winemaker and by ‘57’ and ‘58’ vintages -when Vittorio was ill- Deen made his move, doubling the size of production.

Through the 1960’s a determined Deen De Bortoli embraced innovation, new technology and the growth in table wine consumption that was then occurring in Australia. In spite of his father’s urges for caution, Deen pushed ahead with modernization and expansion, installing new equipment and tank space for much larger capacity. Family lore has it that Deen was strategic. Usually waiting until his father had to go away on a business trip or went on a holiday, to have the new equipment installed. This was done in order to keep the ongoing disputes between father and son to a minimum.

Deen De Bortoli took the business from a successful cottage winery to a large and modern wine company, expanding the business to cater to an increasing national audience of wine drinkers.

Noble One

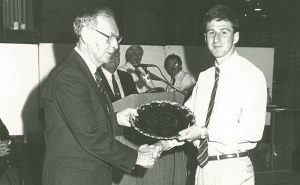

Deen married his wife Emeri in 1958 and over the next decade the pair had four children, all would grow up with a keen interest in the wine trade. Son Darren studied Oenology at Roseworthy, graduating in 1982, he went straight into the family business.

Darren has said, that when he went to Roseworthy, with all the students living together, all they ever talked about was winemaking, they lived and breathed it. When he returned to Griffith he was headstrong and ambitious, just like his father before him. He was keen to experiment with botrytis and produce a sweet wine in the French style of Sauternes and he wanted his father to give him his head. Most in the region, the winery, and even some in the family found this idea to be complete folly.

In 1982, with the support and guidance of his father Deen, Darren created the iconic dessert wine ‘Noble One, Botrytis Semillon’. The wine was quickly recognized as one of Australia’s greats and was named Best Botrytis Wine at the International Wine & Spirit Competition in London, in 1985.

Australia’s most celebrated wine judge and critic, James Halliday has since written:

‘I have no problems in placing the De Bortoli Noble One alongside Penfolds Grange, the great north-east Victorian fortified Muscats and Tokays, the 20-year-old Lindeman’s Semillons, the similarly aged Leo Buring Rieslings, and the best Petaluma Chardonnays, as Australia’s greatest wine styles.’

Today -as the wine approaches forty vintages- it has collected over 420 gold medals and 130 trophies in local and overseas wine shows, firmly cementing its place as one of the world’s greatest dessert style wines.

De Bortoli was now on the global stage and the business continued to grow and meet the opportunities afforded it; soon being recognized as one of the great family wineries of the world.

For the ambitious Darren De Bortoli this wasn’t enough, when he was at Roseworthy all the talk and excitement had been around Australia’s emerging cool-climate regions. He demanded the company buy a vineyard in the Yarra Valley, one of Australia’s most prestigious and successful cool-climate regions. His father Deen did not agree and once again a father and son feud erupted over a younger De Bortoli’s bold intent.

In 2011, Darren retold the story to journalist Nick O’Malley of the Sydney Morning Herald, who wrote ‘Deen resisted and Darren threatened to quit. On one occasion his mother, Emeri hid the keys to all the family vehicles.’ Eventually, Deen came around and today the family owns over 240 hectares of prestigious vineyard, a state-of-the-art winery, and a magnificent restaurant in the Yarra.

Darren’s sister, Leanne, and her winemaker husband, Stephen Webber successfully established De Bortoli Yarra Valley Estate. This was followed by vineyard purchases in the King Valley, Heathcote, the Hunter Valley and Rutherglen. Since Deen finally gave his tacit approval, De Bortoli has again seen its business double and then treble in size.

Today, it is the sixth-largest wine producer in the country and the second largest family-owned wine company. As the family approaches a centenary of wine production in Australia, De Bortoli is firmly established as one of the world’s great wine dynasties and one of Australia’s finest and most successful wine producers.

17 Trees

Amidst all this growth and success, Darren told WINE magazine, “for a family-owned company looking to create a sustainable business for future generations, environmental sustainability has become an integral part of the De Bortoli vision and philosophy.”

In 2006, they joined the NSW Government’s ‘Office of Environment and Heritage’s Sustainability Advantage Program’, which has enabled the company to collaborate on sustainability issues with both the government and local businesses.

In 2012, they received a grant from the Australian Federal Government’s ‘Clean Technology Food and Foundries Investment Program’, which complimented the efforts of the family to raise $11 million to realize their ‘Our Future for a Carbon Economy’ project.

The company has installed the largest solar panel array for any winery in the land, resulting in an energy gain of 264,814 kilowatts.

In 2014, De Bortoli were recognized as a ‘Sustainability Advantage Gold Partner’ for their environmental contributions and leadership in the field. The same year, they received recognition for ‘Excellence in Sustainability’ at the Griffith Business Chamber and NSW Business Chamber Awards and a similar award in the ‘medium to large business category’ at the New South Wales Green Globe Awards.

Recognition is not limited to this country. The wine producer also received the ‘Sustainability Award’ at the 2011 Drinks Business Green Awards in Europe. In 2018 the winery is named Winery Innovator of the Year by the International Wine and Spirit Competition in London for a fully integrated innovation in wine.

In 2019, De Bortoli Wines added to its list of accolades by being recognized in the top 10 of the Australian Financial Review’s BOSS Most Innovative Companies List – the only winery to be named in the competition.

One of De Bortoli’s first sustainability projects started in 2008 and was to plant 17 trees for each company vehicle it purchased, in order to offset the carbon effects of their company fleet. This eventually led to the development of the wine brand 17 Trees, in partnership with the non-profit organization, ‘Trillion Trees’. Trillion Trees has been planting trees since 1979, with the vision to plant 1 trillion trees.

With the 17 Trees label, De Bortoli pledges that for every 6 bottles sold a tree will be planted; at the time of filing this story their website shows they have planted over 36,000 trees, (which equates to over 200 thousand bottles have already sold since the 2020 launch).

The wines are officially stamped as sustainably produced, using lightweight glass, recyclable, vegan friendly and certified as sustainably grown. There is a Chardonnay and Pinot Gris and a Shiraz in the range.

17 Trees, Pinot Gris, 2020

Fruit is sourced from the Riverina and King Valley regions of Australia, 2020 was a very challenging vintage, with drought, heatwaves and large bushfires impacting many regions. This wine is light, crisp and refreshing, with zippy, lemon acidity wrapped around a tropical fruit mid-palate. Partial barrel fermentation and a portion of extended lees contact give some mid-palate richness and wheat husk and granola notes, adding a touch of welcome complexity.

17 Trees, Shiraz, 2019

Fruit is sourced from the renowned red Cambrian soils of the Heathcote region. A pure, fruit-driven style with concentrated plum and sour cherry, hints of dark chocolate and a subtle but effective line of mint and eucalyptus running through the wine. Medium to full-bodied, with good flavour intensity, nice acidity and an attractive ‘freshness’ on the finish.

I think one of the greatest talents of this family of grape growers, winemakers and wine people, four generations in, has been its ability -over the last 90 plus years- to grasp where the industry was headed, and clearly divine what needed to be done for it to prosper going forward. For some time now, Darren and the family have understood that this is no longer just about the quality of what is produced, how many litres are sold, or how much revenue it brings in. Now, it is very much about the environment in which the wine is produced and the impact the business has on nature all around it. What has become critically important to the family, is creating a future that can sustainably accommodate the generations of family and friends to come: just a few harvests away from their 100th vintage, that is a credit to them that we can all celebrate.