The Rangoon Tea House and Me

“Monsieur Thirsty Bedford”

In my travels in Indochina, I had been given an identification paper describing me as Louis (sic) Norman, writer, commissioned by Jonathan Cape Limited of Thirty Bedford Square. By a slow process of compression and corruption, I finished the journey as Monsieur Thirsty Bedford, which, as the name and description had been recopied about twenty times, I did not think unreasonable.

Norman Lewis -Golden Earth, Travels in Burma, 1954

1973

I recall the very first time that I heard about Burma, it was in primary school, grade four to be exact. It was on the outer fringes of what could then only barely be called suburban Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. I was about eight years old, geography class. We were learning about the countries of our region, Southeast Asia. My teacher skipped over a country whose borders resembled (to me) the side-on profile of a long-tailed butterfly. “That’s Burma!” he eventually explained again, at my asking. He told me no one could go there, that it had shut itself off from the rest of the world, a hidden country, trapped in time. I sought more information, but he had very little for me to go on.

To my young ears this all sounded very exciting, a place part mysterious, part marvellous; in that moment my mind decided to lay down a bookmark. I knew I wanted to remember this place for something later on, and I have never forgotten that moment.

1998

Escaping the grind of corporate travel, and the responsibilities of executive management on my somewhat burdened and stressed young shoulders, I decided to escape to Burma for a few weeks. A place I had always wanted to go, (for unexamined reasons that I did not really understand). The trip was to be on my own, with nothing booked but an airline ticket, no fixed plans beyond a vague notion that I might visit a few of the places that, until now, I had only read about in books.

I was heading to a land where I did not know a single person, where my phone would not work, a place not run by a government but by something called SLORC, the very name suggesting something between menace and malevolence, and I could hardly wait.

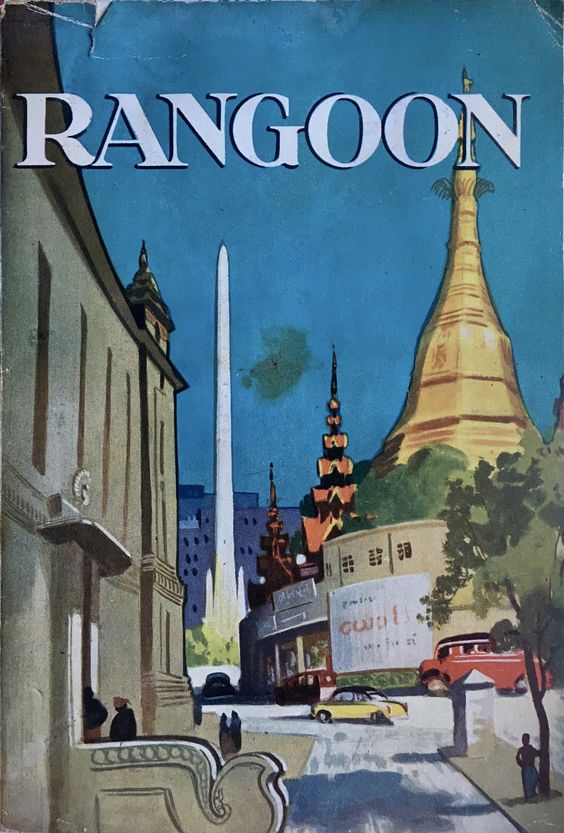

Burma

In Rangoon, I knelt before the Shwedagon, and bathed in its golden glow, I marvelled at its wonder. To this very day I make pilgrimages here to feel its spirituality, to experience the aura and the awe. I then went down to the Sule and tried hard to listen very carefully to its ghosts.

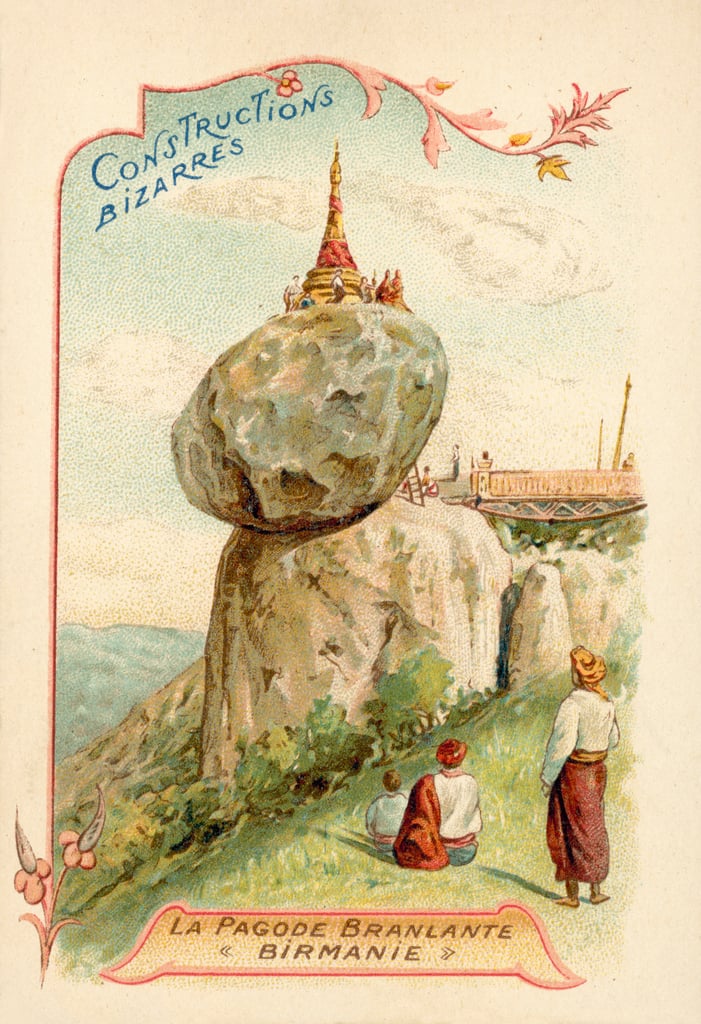

I climbed Mount Kyaiktiyo, to place a tile of gold on its ‘miracle,’ a small pagoda atop a giant rock the shape of the hermit Taik Tha’s head. Now wholly golden in colour from centuries of devotion, the giant boulder hangs precariously over a ledge atop the mountain.

An illusion, the whole ensemble looks sure to topple down the mountainside at the slightest disturbance. People here believe that it balances on a single hair from the Buddha’s head.

I sidled across narrow mountain pathways and crawled through spaces I would no longer fit, to toss coins into the crow’s beak and worship at tiny temples in little caves all over the mountain. I saw vendors in bamboo stores like balconies hanging off the mountain, selling nepenthes of snake, tree bark and roots, I saw large pieces of elephant hide hanging up for sale, I saw fortune tellers, shaman, and all manner of magic, good and bad.

I travelled along a magical road, gliding on the merit of others, to sit with a living weizza, the Pa-O monk/saint, Thamanya Sayadaw U Vinaya. This was before he decided to move on to higher realms, before they put him on display in a glass box and before his remains were stolen and whisked off into the night. We sat and talked about meta at the base of his hilltop sanctuary, in the then Karen State. At his invitation, I climbed up the hill to enjoy a vegetable curry, made in giant woks and infused with love and compassion, given free to all who came.

From atop this little hill, I looked out across the plains to horizons so far away they shimmered as if all was illusion, and I saw a flat, dusty, shimmering land, hammered gold under a relentless sun. The next day I would leave my guide and his wife and head further into the heart of darkness alone. As I examined the prospect of danger, I realized that I did not fear whatever lay ahead, because finally, now, I was truly alive.

I sailed down the Salwin River on an old paddle steamer, a relic of a colonial past, all the way to Kipling’s Moulmein, from where I was then bound for Thanbyuzayat.

The Kaka Saing in Old Moulmein

In Moulmein, Mon State, early on my third morning, I was loitering at a dusty bus stop, waiting for a bus ride that would take me further into parts unknown. I was early, way too early. Eventually, I was approached by a short, thin man dressed in the familiar longyi, t-shirt and a tight, small jacket that highlighted the thinness of his shoulders. He had salt and pepper hair, a wispy, untamed white stubble, and an involuntary smile that revealed the beetle nut stains on his few remaining teeth. He was weathered but not quite elderly, and he was talkative but not quite proficient in a language left behind by an uninvited guest.

He managed to convey to me that the bus would not be coming for quite a while, and invited me to have tea with him in a traditional Burmese tea house -that turned out to be just across the road.

With little else to do I happily agreed, even though my short time here had already taught me to expect that a petty grift, or a more direct approach for donation would soon surely follow.

The teahouse was a small, unpainted concrete room, the ceiling stained with smoke, the walls smeared with ash and splashed with the fiery red stains of betel quid. Low stools tested knees, ankles, and hips; dust, smoke and steam hung in the air, as men in Longyi huddled over low tables, cheroot-stained fingers curled around tiny, chipped cups.

I misjudged my teahouse companion, who merely wanted to talk and learn a little about my travel plans, background, motivation for coming to Burma, and my intentions whilst I was here. I had nothing to hide and so happily indulged in my host’s inquisitiveness.

When I returned fire with a few questions of my own, I asked him where he worked, without hesitation he told me he worked at the large military base just south of town, known as the southern command post. It quickly dawned on me that my new friend may not be merely polishing his language skills, and so, I asked if he was just here to check up on me; he folded his palms out in supplication, smiled calmly and confided yes, that was indeed why we were here.

Sipping tea with this stranger as the low morning sunlight carried its beam through the splintered, cracked slats of a glassless window. A single fan whirring, clacking, and teetering on its stand -as though it was angry at something in the room- and all of a sudden it began to feel like an interrogation, and I decided morning tea was over.

When the bus finally arrived, it turned out to be a small pick-up truck with a metal cage and a canvas roof, little wooden stools -even tinier than the ones in the teahouse- strewn around the tray in back for people to sit on. To this day, my head still spins at how many people we managed to fit in the back of that pickup, regularly stopping to collect more and more people along the way. I was bound for Thanbyuzayat, the end of the infamous Burma railway. In the mid 90’s there wasn’t much here, no people, just an old train engine wreck and a couple of ragged mannequins in tattered uniforms. I felt the souls here, still in shock, whirling about like tumbleweeds trapped in the desert. It was a desolate place, the end of the track felt, fittingly for me, like the end of the Burma road.

My memories of 1990’s Burma then are of a haunting, breathtaking beauty, of smiles barely able to cover the strain, and of a tension that -like its humidity- was an invisible, heavy, wet blanket, under which its people were trapped, stifled: an entire nation desperately trying to poke its head out from under this weight; gasping, hoping to finally suck in some of that clean, fresh air of freedom.

2019

It would be over twenty years before I would once again prostrate myself in front of the Shwedagon and allow myself a few quiet tears, the kind of involuntary, Cartesian tears when your own soul is thanking your body for bringing it back here. By now, young people in Myanmar were dancing in the sunshine, floating on air, a smiling union, their cheeks ruddy with the nourishment of freedom and opportunity.

Then all too soon, as people watched young ladies doing aerobics in the morning sunlight on their television sets and handphones, one could just make out in the background the ominous, heavy quilt being pulled out once more- to be drawn up over a people, over an entire country, plunging it back into darkness, uncertainty, and fear.

The Third Place

Urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg was born in the United States of America in 1932, he is Professor Emeritus at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the University of West Florida in Pensacola. He received his B.S., Mankato State University, 1954; M.A. at the University of Minnesota in 1965; and his Ph.D. at the same University in 1968. He is known for coining the term the ‘Third Place’ and writing about the importance of public gathering spaces in community-building, and for a functioning civil society, democracy, and civic engagement.

Our ‘first place’ is the home and our ‘second place’ is our workplace, (where people often spend most of their time). In either of these spaces, we are concerned or preoccupied with family matters, chores, tasks, and matters relating to our loved ones or careers.

Oldenberg saw these ‘third places’ -a café, a bakery, a wine bar, or beer garden- as anchors of community life, where we facilitate and foster broader, more creative interactions. These are places where we relax in public and where we not only encounter familiar faces but where we also can make new ones from outside our circles. Oldenberg said that “third places offer a neutral public space for a community to connect and establish bonds. Third places “host the regular, voluntary, informal, and happily anticipated gatherings of individuals beyond the realms of home and work.”

We may well recall great European films, where a minor character in an old black and white movie sits in the recesses of a French café, spouting philosophy to an intrigued, (or bored) ingénue. Third places like these are also important meeting points for ideas and conversations and in Cambodia especially, have become places where students can gather to study with friends or where young entrepreneurs can gather to discuss, weigh up, and test concepts.

Scholars determined that Oldenburg’s third place needed eight characteristics:

Neutral ground

Occupants of third places have little to no obligation to be there. They are not tied down to the area financially, politically, legally, or otherwise and are free to come and go as they please.

A Leveler (a leveling place)

Third places put no importance on an individual’s status in society. One’s socioeconomic status does not matter in a third place, allowing for a sense of commonality among its occupants. There are no prerequisites or requirements that would prevent acceptance or participation in the third place.

Conversation is the main activity

Playful and happy conversation is the main focus of activity in third places, although it is not required to be the only activity. The tone of the conversation is usually light-hearted and humorous; wit and good-natured playfulness are highly valued.

Accessibility and accommodation

Third places must be open and readily accessible to those who occupy them. They must also be accommodating, meaning they provide for the wants of their inhabitants, and all occupants feel their needs have been fulfilled.

The regulars

Third places harbor a number of regulars that help give the space its tone and help set the mood and characteristics of the area. Regulars to third places also attract newcomers and are there to help someone new to the space feel welcome and accommodated.

A low profile

Third places are characteristically wholesome. The inside of a third place is without extravagance or grandiosity and has a homely feel. Third places are never snobby or pretentious and are accepting of all types of individuals, from various different walks of life.

The mood is playful

The tone of conversation in third places is never marked with tension or hostility. Instead, third places have a playful nature, where witty conversation and frivolous banter are not only common but highly valued.

A home away from home

Occupants of third places will often have the same feelings of warmth, possession, and belonging as they would in their own homes. They feel a piece of themselves is rooted in the space and gain spiritual regeneration by spending time there.

The Whispering Place

The tea plant Camellia sinens is native to East Asia. The history of tea originated in the borderlands of southwestern China and northern Myanmar, where tea was consumed as a medicinal drink. It was introduced to the West by Portuguese priests and the British introduced commercial tea production to British India, in order to compete with the Chinese monopoly.

In modern-day Burma, they call tea houses laphetyay saing (လက်ဖက်ရည်ဆိုင်), and they can be found in cities, country towns and villages across the nation. Whilst they emerged during the British colonial era, they soon became places for locals to meet, discuss intrigues, air suspicions, share conspiracies, plot maneuverings, and collude over their secrets. Later they were infiltrated by undercover agents, informants, and opportunists so that the dynamics of these spaces would change once again. Now, armed with laptops and mobile phones, tea houses are a place for the conversations of students, artists, philosophers, and free thinkers, or just a place far from the madding crowd, to sit and relax and chill. It seems that you are never far from a cup of tea in Myanmar.

Burmese milk tea is made using strongly brewed black tea, evaporated milk, and condensed milk, similar to Hong Kong-style milk tea. Fresh milk, cream and cane sugar are also optionally added or substituted as ingredients. The base of Burmese milk tea is strongly brewed using black tea leaves, which are simmered in water and a bit of salt, typically between 15 and 30 minutes. The tea base is then combined with evaporated and condensed milk, and ‘pulled’ in a manner similar to teh tarik, to create a frothy layer and to cool the beverage. (Various sources.)

The Rangoon Tea House

In 2012, Htet Myet Oo returned to the place of his birth, Myanmar. He had been raised in the United Kingdom for the previous 20 years. Now 22 and armed with an economics degree from a London University, he possessed an innate desire to connect with the place of his birth and ancestry.

Two years later, he launched the Rangoon Teahouse, a curious, nostalgic, yet thoroughly modern, and wholly satisfying take on Burmese hospitality, its history, its diversity, its charm, and its quality. CNN has named it one of the world’s eleven best teahouses: https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/worlds-best-tea-houses/index.html.

Rangoon Tea House calls itself a modern Burmese tea house in the heart of the city, it is indeed a celebration of the city’s cultural history and culinary diversity. From the wealthy Jewish merchants who came from Iraq to migrants from Bombay, the British, or the Fujian Chinese who arrived in the early 1900s, the city has been home to multiple cultures, languages, and customs. Within the Union itself there are many tribes of people with their own vastly differing cultures and cuisines, the Shan, Pa’O, Intha, Mon, Kachin, Chin, Karen, Wa, Naga, and many, many more. The Rangoon Tea House is a cultural melting pot, in the form of an eating institution that is a Tea House.

Of course, Myanmar’s great strength is its diversity -even if it hasn’t quite managed to realize and come to terms with that itself. It is this rich history and complex diversity that makes it so fascinating, alluring, and exceptional, this is something to engage with, share in, celebrate and enjoy. Diversity is not adversity, it is where we learn, grow, revel and shine.

The Tea House Building in Golden Valley was designed by renowned artist and architect Sayar U Mra at Studio Pyinkadoe. The carpenters were all from Rakhine state and used only traditional methods of carpentry to erect the structure, with all of the windows and doors being handmade; the project took over 20 months to complete. Twenty tonnes of recycled teak and over ten thousand recycled bricks were used during the building process.

No new furniture was purchased for the opening with all of it being a part of Ko Hte’s collection. The tea bar is the longest in Yangon and was formerly used in a German members club in the early 1900s, before moving to a textiles store in Bago, until 2017. You can still find the brass fabric ruler behind the coffee machine.

Founder Htet Myet Oo has said that growing up away from Burma, where he was born, eating Burmese tea-house food was always a cause for celebration. A hot bowl of Mohinga, a freshly made Nan Gyi Thoke – were only had during times of celebration, or visits back to the homeland to visit grandparents.

He notes that what makes a tea house begins with the simple ideology; “what you see, smell, and feel are all as important as what you taste”. The place can rattle and hum with café noises: the clang of pots and pans, the clinking of glasses and teacups and the buzz of vibrant chatter, all adding to the soundtrack and unique atmosphere of this very special space.

An eclectic menu offers Shan classics, Cantonese dim sum, Southern Indian Dosa, Bao buns, Gyoza and more, along with a wide variety of Burmese teas. The menu, and indeed the whole place, is brimming with nostalgia, adventure, new takes on old classics, and what it means to be Burmese and two decades deep into the new millennium.

The great magic of the Rangoon Tea House is to take the faded memories and disappearing history of those too young to have lived it, who only learned it through the folklore and legends told to them by their grandparents and loved ones, and then present it to them in a living, modern and relatable way. History as inspiration, recycled, repurposed, and reinvented. That is some achievement, and perhaps it takes a heart made fonder by absence to have the focus and determination to come home and get it done. Whatever the motivation, the Rangoon Tea House has certainly nailed the brief, gloriously.

The Rangoon Tea House is part of my connection to Burma, I travel to the country every month for work, and because my heart desires it. I work in the enchanting and rural Shan State, so my trips involve a night or two in Rangoon at the beginning and end of each journey. I have made lovely, cherished friendships here and have a great time catching up with people and visiting new venues around town. Nurturing these friendships is important to me, as is tapping into the cultural pulse of the city.

I have two routines that have become absolutely necessary for me when I am in Yangon. I stay in the same room, in the same hotel, I do this because from its giant glass window, I can watch the sun rise up in the east to wash the Shwedagon in the glorious glow of a new day’s first light. I then walk to the tea house, where I order duck empanadas, pork belly bao and a fresh lime juice, then I take out my laptop and I begin to write, to the gentle sounds of a city awakening, it is pure Zen.

Once I have achieved a good deal of writing or, I’ve had a breakthrough, I reward myself with a slice of burnt Basque cheesecake, clotted cream, and a mug of café latte, this is unconditional love on a plate.

It is the small things, the routines and habits that help us to feel like we belong, feel connected, and feel like we are a part of the fabric of a place.

Many, many generations ago, an ancestor of mine was unjustly ripped from his family and sent as far away as any mode of transport at the time could take him; sent to burn in hell for all damnation. Instead, he managed to make a life for himself and eventually, to raise a family. What this has meant for me, is a soul condemned to wander the earth without ever having anywhere to belong to, no land that is my spiritual home.

However, pity me not for this is not a curse, it feels much more like a blessing. As you travel your heart grows and grows, so that you are able to cleave off large chunks to leave wherever it desires you to. My motto is to leave all the love you can, and you can then feel it with you forever. Burma is always in my heart, always with me, so that whenever I am there it feels like a part of me, and whenever I am not, it still feels like a part of the tapestry that is my home.

“I do not believe that the accident of birth makes people sisters and brothers. It makes them siblings. Gives them mutuality of parentage. Sisterhood and brotherhood are conditions people have to work at. It’s a serious matter. You compromise, you give, you take, you stand firm, and you’re relentless…And it is an investment. Sisterhood means if you happen to be in Burma and I happen to be in San Diego and I’m married to someone who is very jealous and you’re married to somebody who is very possessive, if you call me in the middle of the night, I have to come.”

Maya Angelou

My love for Burma, (Myanmar) is -given the geo-politics- always precarious and threatened, but I know now that it has always been and it is eternal, it is something more than myself, and if it calls me in the middle of the night, then I too must come.

Darren Gall