mono no aware 物の哀れ

Artisan

An Artisan /ˈɑːrtəzn/ (formal), (from French: artisan, Italian: artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects, partly or entirely by hand. Artisans practice a craft and may -through experience and aptitude- reach the expressive levels of an artist.

Artisans were the dominant producers of consumer products before the Industrial Revolution. In the modern age of mechanization and single task production lines, where success is measured via a constant quest to cut costs, improve profit margins, growth for growth’s sake, and an ever-increasing dividend to shareholders. Products are often seen as lacking in finesse, elegance or even quality, with creating a thing of beauty, individuality, and with customer satisfaction in mind as being lost to the realms of high expense and luxury instead of modest, everyday expectation.

Artisans have returned to prominence by a society left disenfranchised and unconnected to the soulless mechanization of goods manufactured by faceless corporate giants who hide behind logos and have little to do with nurturing the care and wellbeing of the communities whose dollars they seek.

Today, to be Artisan is to be family-owned or owned by a small group of like-minded friends, to strive to use the finest, local ingredients or materials wherever possible; to be sustainable in your environment and to make products with your hands, your head, and most importantly, your heart. To love and serve your community, just as they inspire you, and finally; to share with them the exceptional quality of your goods, a result of your commitment, your devotion, and your passion for your craft.

Shokunin

Shokunin is the Japanese word for “artisan” it also implies a certain pride in one’s work.

In ‘The Art of Fine Tools’ by Sandor Nagyszalanczy, sculptor Tashio Odate explains,

“Shokunin means not only having technical skill but also, it implies an attitude and social consciousness… a social obligation to work at your very best for the general welfare of the people, an obligation both material and spiritual.”

Whilst in the Kyoto Journal, Sachiko Matsuyama notes,

“I have never been interested in simply defining what a shokunin is. I believe the complexity of the shokunin spirit exists beyond the confines of an occupation. By drawing boundaries and defining who qualifies as a shokunin, we may be limiting our understanding of the ways in which such spirit is manifested in this world.”

Sachiko is the president and founder of Monomo, which is a self-styled marketplace and storyteller focused on bringing unique, Japanese artisan handicrafts into people’s everyday experiences and creating a deeper connection, appreciation, and deep-felt enjoyment to life.

In this fascinating article for the Kyoto Journal: (kyotojournal.org/culture-arts/shokunin-and-devotion/), Sachiko speaks with five Shokunin hoping to ‘identify some of the unique elements of a shokunin’s life and mentality that are manifested in their work’.

NATURE: Selfless surrender after earnest effort

TIME: Devotion over a lifetime, and over a millennium

COMMUNITY: Beyond the notion of individualism

Shokunin, through their devotion, give us that connection between nature, art, and life, the industrial revolution and global trade broke this ‘interconnectedness’, which has left many of us with feelings of disassociation and emptiness.

We have lost connection to our community and our environment, to our nature and it is becoming increasingly apparent that this is no longer sustainable, for our own wellbeing and for that of the planet on which we inhabit. Contemplate and combine this industrialization and over-production with connection online, in a virtual world where we are constantly corralled, insulated, marginalized and manipulated by algorithms and agendas, it soon becomes easy to understand people’s anxiety and despair.

It is through a selfless commitment to their task, on that reconnects nature to community that shokunin and artisans can help repair the deep cracks in our world and the ever-widening abyss between human and nature.

“In order to make delicious food, you must eat delicious food. The quality of ingredients is important, but one must develop a palate capable of discerning good and bad. Without good taste, you can’t make good food. If your sense of taste is lower than that of the customers how will you impress them?”

Jiro Ono

Many of you will be familiar with a film called ‘Jiro Dreams of Sushi’, about sushi chef Jiro Ono. Jiro started working in a local restaurant at the age of seven, before moving to the kitchens of Tokyo to do an apprenticeship. He became a qualified sushi chef in 1951 and opened his own restaurant in Ginza, Chuo, Tokyo in 1965. Sukiyabashi Jiro is a small, ten-seat restaurant in a subway station serving nigiri ‘Edo style’ sushi. Today, Ono is regarded by his contemporaries as one of the greatest living sushi craftsmen.

In the first edition of the Japan Michelin Guide in 2007, Sukiyabashi Jiro was one of only eight restaurants in the country to be awarded the coveted three stars. In 2019, at the age of 93, Jiro entered the Guinness Book of Records as the oldest chef in the world to hold the three-star title.

David Gelb’s beautiful little Japanese language film with its mesmeric Philip Glass soundtrack was an inspired work of art greater than the sum of its parts. The critical response was overwhelmingly positive and a release on Netflix ensured it was seen by a wide audience. Pretty soon, everyone who was anyone wanted to dine in the little ten-seater in the subway at Ginza.

In 2014, Japan’s prime minister Shinzo Abe hosted United States President Barak Obama at Sukiyabashi Jiro, who, according to the New York Times said of the meal, “I was born in Hawaii and ate a lot of sushi, but this was the best sushi I’ve ever had in my life.”

Danish chef Rene Redzepi is one of the most famous, respected, and awarded chefs in the world today, his three Michelin star restaurant Noma in Copenhagen was voted by Restaurant magazine as the best restaurant in the world in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2014. In 2021 the ‘World’s Best 50 Restaurants’ again voted Noma the best restaurant in the world.

Redzepi, upon seeing the film made a pilgrimage to Jiro’s restaurant where a fascinating conversation ensued.

Redzepi, “How long did it take for you to feel like you became a master?”

Jiro, “Till when I was 50 years old.”

Redzepi, “Between when you started as a teenager to when you were 50, did you ever think of quitting?”

Jiro “No. The only question I asked was – how can I get better?”

Jiro’s dedication is acknowledged by the man himself, repetition; he does the same thing over and over, improving bit by bit…. “There is always a yearning to achieve more. I’ll continue to climb, trying to reach the top, but no one knows where the top is.”

How is this focus achieved and held for over seventy-five years? “Once you decide on your occupation, you must immerse yourself in your work. You have to fall in love with your work. Never complain about your job. You must dedicate your life to mastering your skill. That’s the secret of success and is the key to being regarded honorably.”

Jiro’s eldest son Yoshikazu works for his father and is over 50 years of age, he is a great sushi chef in his own right and as is traditional and expected, he will one day take over the business from his father. His younger brother left to open his own restaurant over fifteen years ago because only the eldest son will inherit the family business. When Yoshikazu is asked if he is envious of his little brother being able to strike out on his own, he simply states that in Japan it is expected of the older son to take over from his father. Yoshikazu simply ignores the question as an irrelevance, his focus is only on his duty.

It can take up to ten years as an apprentice to Jiro before the master starts calling you shokunin and new students spend weeks learning to do tasks like squeezing out a towel properly before being allowed to even approach the kitchen. Senior apprentice, Daisuke Nakazawa, describes in the movie, how he made the chef’s famous Tamago, (omelet) over 200 times, (all rejected) before finally perfecting the dish. Nakazawa openly admits that when his tamago finally received Jiro’s approval he wept like a baby.

In 2016, chef author and travel documentary maker the late Anthony Bourdain was asked by The Guardian newspaper what he would like for his last meal, his reply was that ideally his last meal would be taken alone at Sukiyabashi Jiro. Here he and Jiro San would exchange pleasantries, drink a little too much sake and eat some of ‘the best sushi on the planet’. Bourdain suggested that Jiro would make a ‘22- or 23-course omakase, tasting menu’ for him and just as he was finishing the world-famous and incredibly precise tamago (omelet), he would sag to the floor and “in my last conscious seconds I would know that on this night, no one on Earth had eaten better than me. Pure pleasure.”

The omakase menu at Sukiyabashi Jiro costs around $400 USD and is hand-served over a period of about 45 minutes. It is worth explaining here that the restaurant was recently stripped of all of its Michelin stars, not because anything changed in the restaurant with its food or service, but because the restaurant changed its booking policy. Tired of no-shows, tourists who just wanted to tick a bucket list and were unable to respect or appreciate the place or the food, and most importantly, no longer being able to serve their regulars and their community; the restaurant simply stopped taking bookings over the phone or online.

The guide’s simple logic was that if its readership base could no longer go to the restaurant, then it would no longer be able to list it in its guide. No one at Sukiyabashi Jiro seems to mind, given it is a ten-seat restaurant owned by the world’s most famous sushi chef, perhaps Jiro is even a little content, now that his restaurant can serve his regulars and his local community once more.

In her book ‘Sushi Shokunin: Japan’s Culinary Masters’, Tokyo-based, James Beard Award-winning photographer and author Andrea Fazzari profiles twenty of the most celebrated sushi masters on the international Japanese food scene. In Japan, cooking often bears aesthetic value, and the making of sushi is exalted as one of the finest culinary crafts. In her introduction she states. “Concurrently, they are altruistic leaders, teachers, and artists of tremendous spirit and skill, who strive for excellence not only for themselves but also for the benefit of others … This dedication to a lifelong pursuit of the highest level of mastery … affords all types of shokunin a respected and integral role in Japanese society.”

In a recent interview, Fazzari explained, “Ikigai is the Japanese term for ‘one’s purpose in life,’ ‘one’s reason for being,’ what motivates you to get up in the morning. All of these sushi shokunin are guided by their ikigai, and live in the disciplined and passionate pursuit of their craft. As artisans with acute attention to detail and tremendous skill, they never stop striving for further improvement. Within this daily “doing,” creating what they love, they attain a level of synchronicity that can be equated to a kind of spirituality where the meaning of life can be found.

“With their (shokunin) work existing beyond themselves in a vast cultural landscape, they have a unique humility that allows them to work with centuries of wisdom and the forces of nature. These aspects are fundamental to who shokunin are. Although each shokunin manifests these qualities slightly differently, the shared spirit connects their lives and works like a gradation of colors. Each of them hold histories and stories that cannot be disregarded. I am always awed to realize that the spirit of shokunin transcends their individual existence. Beyond their magnificent individual radiance, there is always devotion to the larger cosmos.”

Sachiko Matsuyama

Wabi Sabi

Wabi Sabi is more than a Japanese aesthetic; it is a way of living and a way of viewing the world, it is (to me) profound, it is Zen and it is beauty. Wabi-sabi is the acceptance of transience and imperfection, and it is finding the wisdom, peace, and beauty within these paradigms, which gives rise to a sense of melancholy and a spiritual longing.

Zen and Mahayana philosophy espouse acceptance and contemplation of the imperfection, impermanence and fluctuation of all things, art influenced by such philosophy embodies a wabi-sabi aesthetic, this includes artistic rituals such as the Japanese tea ceremony.

Kintsugi

‘Kintsugi’ is another Japanese wabi-sabi art form, known as the ‘art of imperfection’ it is the repairing broken pottery with gold. The philosophy here is that an object becomes more attractive when repaired because its newly highlighted cracks tell the story of the journey and uniqueness of the object, now made more beautiful by its history, its scars, and its imperfections. The history of Kintsugi has been dated back to the Muromachi period, (1336 to 1573) and the Shogun of Japan, Ashikaga Yoshimitsu.

In the flush of youth, we are something akin to physical perfection, unbreakable, impenetrable, lithe, flexible, bendable: skin bristling, veins coursing with restless energy, latent potential, like foals in an open field, undisciplined, wayward, frisky, and free. Our minds are like sponges, full of parts unknown, tabula rasa, wonder, and acceptance. No journeys, no stories, no mountains climbed, no deep dives, no free-falls; knees un-scraped, head unbowed, heart un-bruised. Our minds; full of dreams, ideas, ambition, hope, faith, and belief.

Then life’s blacksmith’s get a hold of us, (work, family life, relationships) lighting their fires and banging us up, doing their damage, until we no longer bend but crack, no longer expand but fragment, no long realign but shatter and fall. In the philosophy of Kintsugi, we must not despair of these aspects and events that shape our lives and forge our character. We should not seek to hide this damage but instead, like the precious veins of gold in a piece of repaired pottery, make the scars of repair beautiful and strong.

Appreciate the beauty of all things, especially the great beauty that hides beneath the surface of what seems to be broken. It is through the imperfections of art and the beauty of our scars that we can appreciate our own imperfection and vulnerability, and we come to respect it in others.

Wabi Cha

“Though you wipe your hands and brush off the dust and dirt from the vessels, what is the use of all this fuss if the heart is still impure?”

Sen no Rikyu

The Japanese tea ceremony, known as ‘chado’, (The Way of Tea) or, cho no yu, is a centuries-old, cultural ceremony involving the preparation and serving of matcha, (powdered green tea). The art form of presenting the tea ceremony is known as ‘otamae’; the practice with leaf tea, (sencha) instead of powder is known as ‘senchado’. Chadō is one of the three classical Japanese arts of refinement, along with kōdō for incense appreciation, and kadō for flower arrangement.

Tea ceremonies are either informal, known as ‘chakai’ or the more formal ceremony ‘chaji’:

A chakai offers a simpler hospitality that comprises confections, thin tea, and perhaps a light meal.

A chaji is much more formal ceremony and will encompass a full-course kaiseki, followed by confections, thick tea, and thin tea. This type of ceremony is expected to take at least four hours.

Zen Buddhism has close associations to the tea ceremony; the Nihon Kōki is official Japanese history text commissioned in the year 819 AD, by Emperor Saga. Completed in 840, it is the third volume in the Six National Histories and covers the years 792–833. It contains the first mention of tea in Japan when a Buddhist monk named Eichu returned to Japan from China with some tea which the test says the monk personally served to the Emperor in 815. A year later, by royal edict tea plantations were being cultivated in the Kinki region of Japan.

Towards the end of the 12th century the style of tea preparation known as ‘tencha’, where powdered matcha tea is placed into a bowl, hot water added, and then the two are whisked together, was introduced by another Buddhist monk returning to Japan from China, whose name was Eisai. This time, the monk brought seeds back with him, and this produced tea that would eventually be considered the finest in all Japan. Tea in this manner was being used for religious rituals in Buddhist monasteries.

Part of the philosophy of Zen Buddhism involves mindfulness and the concept that simple actions can lead to an awakening of our spirits, the philosophy of zen: mindfulness, transience, acceptance complemented by the main principles of the tea ceremony: harmony, respect, tranquility.

During the time of the Kamakura shogunate, (1185 to 1333) tea and the ceremonies associated with it became something of a status symbol amongst the warrior class. Tea ‘tasting’ parties became popular and would often involve contests where teas were tasted blind and extravagant prizes were awarded for those who successfully identified the best quality teas.

The halls that hosted Japanese tea ceremonies became lavish and vast in size, the ceremonies themselves were all about extravagance and expense, including imported wares and utensils of Chinese origin known as karamono. Tea ceremonies were little more than an opportunity for important figures to come and show off their status and power, they now seem to have had very little to do with the philosophies of Zen.

A young attendant at the Shōmyōji, Buddhist temple in Nara named Murata, Juko encountered the unruly ‘tocha’ parties known as “four kinds and ten cups”, in which participants tasted three cups each of three different teas and a single cup of a fourth variety and had to guess which region each tea was from. The contests could be rowdy and often involved alcohol and gambling. Prizes included silks, weapons, gold, and jewelry, which gave the participants a reputation for excess and indulgence.

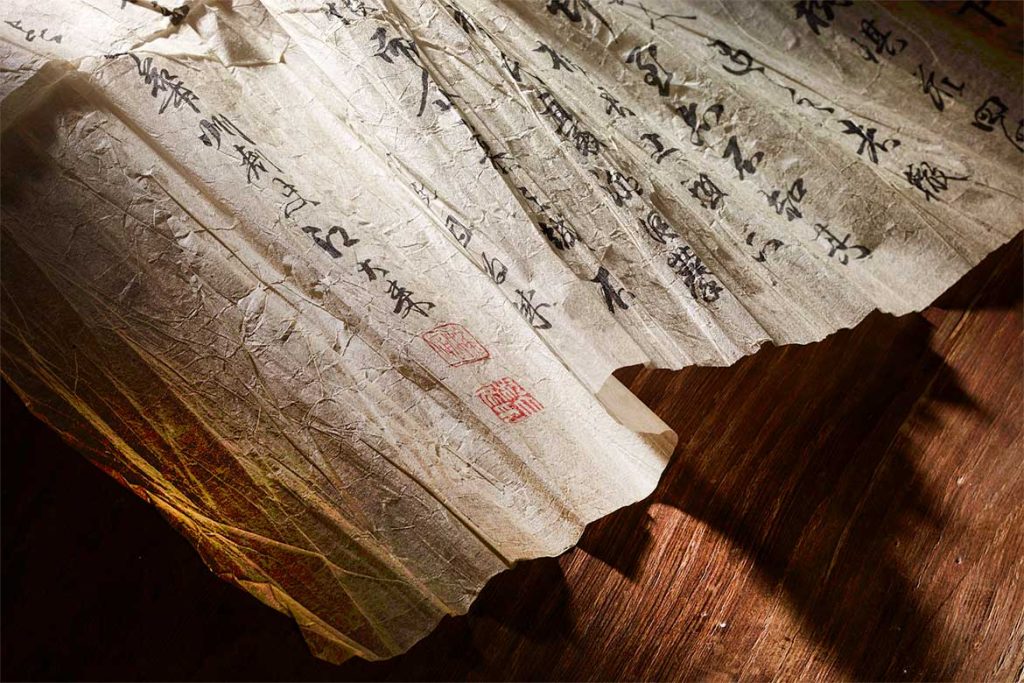

Juko had little interest in the parties themselves but, he became interested in the tea itself as a stimulant to help him with his studies at the temple. Jukō moved to Kyoto and studied Zen under Ikkyū Sōjun who taught that “the Buddha dharma is also in the Way of Tea” which inspired Jukō’s creation of his own type of formal tea ceremony. The resulted in Juko being presented with a piece of calligraphy by Chinese Zen Master Yuan Wu as confirmation of his enlightenment. Juro set out his theories on the tea ceremony in a letter to one of his students, which has become known as the ‘Kokoro no Fumi, (Letter of the heart) which laid out the foundations of the tea ceremony that exists to this day.

Juko made use of Japanese utensils instead of the expensive imported ones from China, he had a fondness for the rustic, unglazed, and somewhat imperfect, local pottery. He emphasized four values as part of the ceremony, ‘Kin’, humble reverence, ‘Kei’ respect for the food and drink, ‘Sei’ purity of body and spirit, ‘Jaku’ a Zen concept of calmness and freedom from desire. He was also in favour of a much smaller tea house to create a more spiritual environment for the ceremony.

Takeno Joo studied under students of Juko and continued the development of simplicity and minimalism in the tea ceremony, emphasizing the concept of Ichi-go Ichi-e which describes the concept of valuing the unrepeatable nature of a moment and the need to therefore treasure every meeting.

Joo was a teacher of the man who codified and would come to be regarded as the father of the type of tea ceremony known as ‘Wabi Cha’, Zen Master Sen no Rikyu, who would become tea master for two of Japan’s greatest samurai and daimyo during the Sengoku period.

Sen no Rikyu had the most profound influence on the Japanese ‘Way of Tea’ and is considered to be the Zen master who had elevated chanoyu to an art form and a profound philosophical and spiritual ritual. Building on the concepts of Juko and Joo, Rikyu defined and established the wabi cha style incorporating the philosophy of wabi sabi into the ceremony in pursuit of a deeper spirituality. The word Wabi expresses simplicity, impermanence, flaws, and imperfection, Sabi displays and expresses the effect that time has on a substance or object. Together ‘wabi-sabi’ embraces the idea of aesthetic appreciation of aging, flaws, and the beauty of the effects of time and imperfection. The two separate parts when put together, complete each other to express simplicity and the truest form of an object. Wabi Sabi embraces the finding of comfort in purity and a life detached from materialistic obsessions of the world.

For Rikyu, the teahouse needed to be small and rustic, tucked away in a secluded garden, reached via a meandering path that took in trees and stones that would help people to break off from their normal thoughts and connections to the world as they approached it. The door would deliberately be just a little too small, so as to ensure that all who came would have to bow and feel equal to others. The idea was to create a barrier between the teahouse and the world outside. The utensils and accoutrements used to perform the wabi cha ceremony would be simple, locally crafted, unglazed and rustic, some of these were specifically designed Rikyu, who then had them made out of ceramic or bamboo.

Properly performed, the Wabi Cha tea ceremony is meant to promote a sense of ‘wa’ harmony, as you become aware of the nature all around you, and a sense of ‘kei’ sympathy for those in close proximity before finally leaving guests with a feeling of ‘jaku’ tranquility as they, which is one of the most central concepts in Rikyū’s gentle, calming philosophy.

Wabi cha’s fundamental tenet is that better interaction is accomplished in places that have purity and simplicity. In Japan, hospitality entails a person doing their very best to offer their guest a taste of their intentions.

The tea ceremony has changed since Rikyu’s time, yet still embodies the Wabi-cha philosophy; the three most prominent schools of today are Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushakojisenke, all of which trace their roots back to Sen no Rikyu.

“Those who cannot feel the littleness of great things in themselves are apt to overlook the greatness of little things in others.”

Okakura Kakuzo, The Book of Tea

The thing that gets you out of bed each morning and keeps you going each day

Ikigai is an age-old Japanese ideology associated with long life expectancy, especially amongst the people of Okinawa. A combination of the Japanese words “iki” which translates to “life,” and “gai”, which describes value or worth: ikigai is about finding joy in life through purpose.

“The grand essentials to happiness in this life are something to do, something to love, and something to hope for.”

Hector Garcia

Ken Mogi is a neuroscientist based in Tokyo; he has published over 30 papers on cognitive and neurosciences, and over 100 books covering popular science, essay, criticism and self-help. In his beautiful book ‘The Little Book of Ikagai’ he explains that although it is true that having ikigai can bring success, ikigai is not the ‘realm of global recognition and worldly acclaim’. Ikigai resides in the ‘realm of small things, the morning air, the cup of coffee, a ray of sunshine. Performing a task and receiving recognition for it are on the same footing, and only those who recognize the richness of this whole spectrum, can really appreciate it and enjoy it’

Mogi goes on to explain the ‘Five Pillars of Ikigai’ which are: starting small, releasing yourself, harmony and sustainability, the joy of little things and being in the here and now.

He sees these pillars as supporting the framework, the very foundations that allow ikigai to flourish. Mogi also talks about chef Jiro Ono, suggesting that whilst he may ‘possess exceptional talent, determination, bloody-minded perseverance’, as well as a relentless pursuit of excellence in his field, he also has, ‘perhaps above all else’, ikigai.

Dan Buettner is an American National Geographic Fellow and New York Times-bestselling author. He co-produced an Emmy Award-winning documentary and holds three Guinness records for endurance cycling. In his book, ‘The Blue Zones: Lessons for Living Longer From the People Who’ve Lived the Longest’ Buettner explores the five places in the world where people live the longest and calls these locations ‘blue zones’.

Buettner traveled to each blue zones and interviewed the centenarians he found living there, many of whom still loved independently.

He then compiled a list of common traits amongst these people that play a role in living longer:

Food: Simple, predominantly plant-based, and rich in nutrients.

Physical activity: many of these people have their own gardens or work long hours in their fields.

Family and purpose: these communities are based around family values. When people reach old years, they still have a role in the family, for example, they help to raise their grandchildren.

Sense of community: people visit each other and support others in times of need.

One of the blue zones that especially stands out is the island of Okinawa, Japan. When Buettner talks to the elders in the villages of Okinawa they talk about ikigai. They talk about finding something to do that they love, that they are good at, that they are paid or supported for, and that their world needs from them. There is no existential crisis here, these elders are connected, have purpose, they live in the moment, and are for the most part happy in their lives.

Published in the Journal of Epidemiology in 2016 a paper titled, ‘Relationship of Having Hobbies and a Purpose in Life With Mortality, Activities of Daily Living, and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Among Community-Dwelling Elderly Adults’ by Kimiko Tomioka, Norio Kurumatani, and Hiroshi Hosoi clearly established that finding ‘your ikigai’ has been scientifically proven to help people live a longer, happier life.

Feature writer for the Telegraph in the United Kingdom, Luke Mintz recently wrote an article titled ‘To Solve the Puzzle of What Makes Us Happy, Forget the Big Picture’. Mintz noted that for a new generation of happiness scholars it is the small but significant moments in life that were the foundations of happiness itself. Mintz states that it is an appreciation of these small, fleeting moments of fulfillment: a hand, held by a loved one; the sound of rain on the roof as you drift off to sleep. Observing that artists and musicians have long considered these joyful vignettes to be the bedrock of human happiness.

Mogi in his wonderful little book also talks about the importance of starting small and being in the moment, paying attention to every step and detail of what it is you do or create for your community, cultivating a sense of kodawari, which is a commitment and insistence on a certain set of standards and a level of excellence in each small step of the way.

Accept who you are, find your purpose, enjoy your task and feel valued for it, focus on the small joys and living in the moment with them, transcending, being.

To be an artisan is to pour enough of yourself into your art, your craft, into what you are producing, so as to imbue it with certain characters and qualities that are made up of all your training, your knowledge your skill, your emotions, your sensitivities, passions, desires, and dreams and of those that came before you and those that will come after; with the hope that this can in some way be seen, felt, heard or even tasted and smelled by the people who are good enough to buy it. Those people who are part of your community, circle, or tribe; who you care for, and are in turn your inspiration; thus completing the cycle and the true nature of things.