Nature never deceives us; it is we who deceive ourselves.

-Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Masanobu Fukuoka (1913 –2008) was a Japanese farmer and philosopher, he was a trained microbiologist and agricultural scientist and after completing his education he worked at the Yokohama Customs Bureau. In 1937 he was taken to hospital with pneumonia and whilst there had what he termed a ‘spiritual’ experience which changed his entire view of the world. Upon leaving hospital and returning to good health Masanobu quit his job and returned to the family farm on the island of Shikoku in southern Japan.

He had come to, at first doubt and then, completely disagreed the modern, mostly western agricultural practices of his time and wanted to practice and experiment with a new way of farming.

Masanobu Fukuoka began developing an idea he would come to call Shizen noho, ‘Natural Farming’ which some would later refer to as ‘Do Nothing Farming’, Masanobu advocated no tilling, no pesticides no herbicides no pruning, he preached farming methods familiar to indigenous cultures and was an outspoken advocate of observing nature’s principles. He soon found his methods extremely successful and eventually he became confident enough to share his findings with others.

In 1975 he published his seminal work, ‘The One Straw Revolution’ which described his life’s journey, his philosophy and his farming techniques. The book was translated to English in 1978 and a year later Masanobu Fukuoka was an international sensation.

He would spend a great deal of the rest of his life traveling the globe, giving lectures, advising on practical farming, sowing seeds both real and of change, he visited the USA, much of Europe and Asia, China, South America, Africa.

Masanobu’s system is based on the recognition of the complexity of living organisms that shape an ecosystem, he saw farming not just as a means of producing food but as an aesthetic and spiritual way of going about life, the ultimate goal was ‘the cultivation and perfection of being human’.

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner, (1861 – 1925) was himself an immensely influential character with a wide range of influences and a diverse range of interests; he was a literary critic, an architect, a philosopher, a spiritualist, a mystic and a social reformer.

At the age of nine Steiner had what he considered to be a profoundly spiritual experience then at around the age of fifteen he met a herb gatherer on a train, this man, known as Felix Kogutzki conveyed in conversation to Steiner a knowledge of nature that the young man considered spiritual and definitely not academic.

Steiner attended the Vienna Institute of Technology in 1879, he had already studied Kant, Fitche and Schilling and here he was introduced to the works of Goethe. He was invited to be the natural science editor on the Kurschner edition of Goethe’s works, later he would be asked to edit the Weimar editions.

Steiner then went on to write two books on Goethe’s philosophy, the first was ‘The Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe’s World Conception’ which he regarded to be the epistemological foundation and justification of his later work.

The second book was tiled ‘Goethe’s Conception of the World’. During this period, he also collaborated on complete editions of the works of Arthur Schopenhauer and made many contributions to various journals.

After receiving his doctorate in philosophy Steiner then wrote and published his first major work, ‘The Philosophy of Freedom’. This addressed the question of ‘in what sense can humans be considered to be free?’. In the preface Steiner sets out to make it clear that he is strongly influenced by Goethe’s seminal works on learning and knowledge. Steiner’s concepts were similar on freedom to Hegel’s and both believed that an ethical life is the ideal of freedom, which has its basis and volition in self-consciousness.

Having met the not-of-sound-mind, Friedrich Nietzsche and being deeply moved by the experience, (Friedrich Nietzsche was another giant of the philosophy of the age, he was ravaged in later life by syphilis, which first turned him into a raving loon and then left him in a catatonic state) Steiner wrote the book, ‘Friedrich Nietzsche – Freedom Fighter’.

In 1897, Steiner moved to Berlin where he became a shareholder and the editor-in-chief of the literary journal ‘Magazin fur literatur’ the journal struggled and lost support after Steiner’s own strong support of Emile Zola and his famous J’accuse article during the dreadful, Dreyfuss Affair. Although Zola was eventually proven right after almost a decade, his position was deeply unpopular with many at the time.

Upon leaving the journal, Steiner published an article ‘Goethe’s Secret Revelation’, discussing the esoteric nature of Goethe’s fairy tale ‘The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily’. He was then soon invited to speak at a gathering of Theosophists on the subject of Nietzsche. Steiner would continue speaking regularly to members of the Theosophical Society, becoming head of its newly constituted German section in 1902. Annie Besant -whom had taken over management of the society upon Madam Blavatsky’s passing- then formally appointed Steiner the leader of the ‘Theosophical Esoteric Society for Germany and Austria’.

So, by the age of 40 Steiner had undergone what he himself had acknowledged as a profound change, from being someone highly intellectual and event combative when discoursing with others, to someone profoundly spiritual and interested in engaging with people for who they were and seeking with them an esoteric experience of the world.

In Europe, The Enlightenment which spanned the mid 1600’s to the late 1700’s had dramatically changed the lives of many people. It occurred at a time of great scientific breakthroughs and development, changing the very way we thought about the world and our place in it.

It changed the way people were ruled in several countries and it was a world of rationale, reasoning, science and scepticism. Nothing would again be holy and nothing would again be sacred.

Jethro Tull, (1674 –1741) was a pioneering agriculturalist whom did much to bring about the British Agricultural Revolution. His invention of seed drills and horse drawn hoes and the practice of aerating the soils to make them more aerobic met with great success and would be adopted over much of Europe.

However, his non-use of manures and compost soon exhausted the soils, once others started to feed the soils with composting and manures and combined Tull’s mechanized methods a much greater success on a much larger agricultural scale was possible. It also cut down greatly on the required number of full time labour for farmers.

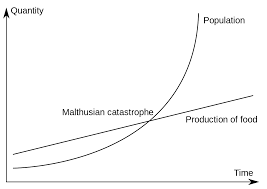

The Agricultural Revolution would take place through the 1700’s and see a dramatic increase in crop production levels in Great Britain and then across Europe. At some point, growth in crop production was outstripping growth in population until the people of Great Britian and Europe were able to break out of what was known as the Malthusian Trap, so named after political economist Thomas Robert Malthus, (1766 –1834). Malthus first made the argument that in “every age and in every state” population increases are limited by the means of subsistence, and that when the means of subsistence increases, population will also increase, and that the population increase will be then limited by “misery and vice”.

The Industrial Revolution, (1760-1840) heralded immense and often dramatic and land workers were able to leave the fields for factories and earn real incomes. Up until then, people’s standards of living never really increased because technological advances and new discoveries only resulted in population growth and not in higher individual incomes. Now, due to the Agricultural and Industrial revolutions the income per person began to dramatically increase, and they broke out of this so called trap.

However, one of the observed consequences of escaping the Malthusian Trap was for many countries and peoples, political upheaval.

So, in a very short space of time we had largely left the land and moved into factories, we had gone from hand producing items to machine production, we had largely abandoned the Christian god as our moral guidance and the monarchy as our absolute ruler and we felt a disconnection, a loss, we had abandoned nature, no longer took owner ship of our skills and the things we produced and we had lost our faith.

The political economist Adam Smith, in his epic, ‘The Wealth of Nations’, (1759) had suggested that in an industrial age there was little need to work together, we simply needed to be more productive, Smith believed that if we each strove to succeed to our own ends then economic and humanist forces would come into play that would benefit the whole as well as the individual.

In other words, when an individual promoted his own self-interest, it benefited all of society. Smith believed in a free market and felt that in a perfect free market where everyone strived to take care of their own needs, all would benefit. However, he did point out that should business or business owners gain too much power and too much political clout then collusion and corruption would be a serious risk.

However, as economies evolved and individuals became obscenely wealthy whilst large majorities of the population remained in poverty or could not find work, people began to question the existence of Smith’s invisible hand that was supposed to be there to help them along. Some even began to suggest it was actually a con.

Alfred Marshall, (26 July 1842 – 13 July 1924) was one of the most influential economists of his time he was an early critic of Smiths attacking him on several points. Marshall argued that humans should be equally important as money, that services are as important as goods and that there must be an emphasis on welfare as well as wealth.

American Noble-Prize winning economist, Joseph Eugene Stiglitz, (1943) contends that, “the reason that the invisible hand often seems invisible is that it is often not there at all.”

‘Every civilization was built on the back of a disposable workforce but, I can only make so many.’

– Niander Wallace, (Jared Leto) Blade Runner 2149

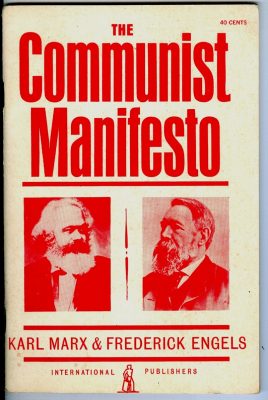

Karl Marx, (1818 – 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His most famous works are, The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Das Kapital (1867–1894). After studying in Bonn and Berlin were he became involved with the group known as the Young Hegelians, Marx moved to Paris in 1843 and commenced writing for a radical leftist newspaper.

Within a year, Marx met the German socialist Friedrich Engels at the Café de la Régence, beginning a lifelong friendship and collaboration. During this time Marx embarked on an intense and passionate study of political economy that he would pursue for the rest of his life.

It was at this time the he formed his views and philosophies on society, economics and politics which would come to be known as Marxism. Marx held the view that human societies progress through class struggle: a conflict between an ownership class that controls production and a dispossessed labouring class that provides the labour for production. States, Marx believed, were run on behalf of the ruling class and in their interest while representing it as the common interest of all.

He felt that the working class where being alienated, isolated and exploited. Marx described the realization that through the industrial revolution people no longer made things they instead merely provided labour in a long line of production, this meant that they no longer could take ownership or pride in their work, that they were no longer transforming the world and were removed from their own nature and this was something of a spiritual loss.

Throughout history there have been great leaps forward in technologies and practices that allow us to produce significantly larger and larger amounts of product and produce but, it seems that with each of these steps there are people who are greatly advantaged and people who are disadvantaged and it is the numbers on either side of this ledger that must be considered. In the modern world it appears these considerations now must be extended to consider the health and preservation of the entire planet on which we all currently exist.