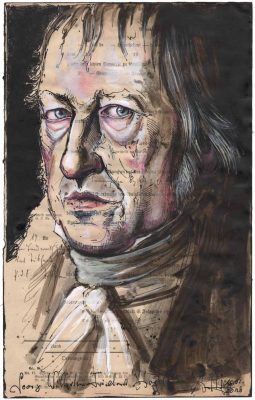

“Nothing great in the world was accomplished without passion.”

― Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

Consumer preferences in wine are a bit like hem-lines in the fashion industry, just as sure as they will rise, they will one day come back down again, for every action there is an opposing reaction. In fact, it seems as soon as there is literally too much of a good thing, our tastes turn in a different direction, desiring that which we are yet to attain.

Take for example some of the markets in Asia, where it seemed that everyone started out drinking Bordeaux until a movement turned its attention to Burgundy and that set off the ripples of change and very quickly it was Burgundy on everyone’s lips and shopping lists. Eventually, people seem to work out what wines they like to drink and that what they prefer might depend on who they are with, what they are eating, what time of day it is or whatever the occasion. However; drinking the right wines and buying the right brands can at times appear to be just as important to some consumers as enjoyment of the wines themselves.

For a time, Chardonnay was the favourite wine of the New World, rich and creamy with ripe peach and butterscotch flavours drowned in buttery, nutty, smoky, toasty new oak. That was until some influential wine scribes pointed out it that often these wines were just way too oaky and lacking in quality fruit. The all of a sudden ‘unoaked Chardonnay’ was a thing! Eventually wine producers and consumers alike worked out that a little oak was not a bad thing and something of a balance was desired in these wines as well as in their markets.

Green, grassy, aggressively acidic and often unripe Sauvignon Blanc was all the rage in the Southern Hemisphere, until a few prominent wine critics pointed out that unripe ‘Sauvy’ was just too green and too aggressive and so, riper, richer more tropical and passionfruit style Sauvignon Blanc were soon demanded by the market. That was until the pendulum then swung back somewhere towards the middle and again it was all about balance. Today, winemakers often resorting to two picks during harvest, one slightly early and one slightly late to give them the opportunity of getting the balance just right in the winery instead of on the vine.

For a time, cool climate Cabernet Sauvignon was all any red wine drinker was interested in, then a few poor vintages and a lot of under-ripe wines with aggressive green tannins saw the market shift dramatically to overly ripe, jammy reds with fine, almost imperceptible tannins and alcohol so high as to be more like vintage ports.

Eventually, technology and common sense prevailed and medium bodied red wines with ripe fruit flavours, fine tannins and moderate alcohol began to find their place at the head of the market.

All these swings in consumer preference and changes in winemaking style; it is like some sort of ‘Hegelian Dialectic’, where there is thesis, then antithesis and finally a synthesis.

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (August, 1770 – November, 1831) was a widely acclaimed German Philosopher and a leading figure in German Idealism, his ‘Phenomenology of Spirit’ (1807) and other works conceptually integrated psychology, the state, history, art, religion, and philosophy.

He was also an incredibly poor writer whose style was as abstract, obscure, complicated, verbose and impenetrable as to be, for many of us, largely incomprehensible. His work can be so daunting and undecipherable that many students of philosophy attempt to avoid Hegel all together, whilst most seem to opt for reading works about Hegel’s work that reading the actual work itself.

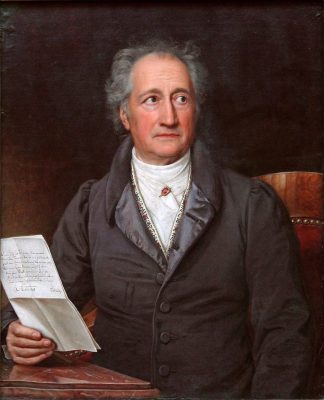

In a lecture delivered by Dr Justin Burke to the Socratic Forum and titled ‘Everything you know about Hegel is wrong’. Dr Burke introduces us to an experiment conducted by Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe on his Daughter-in-Law.

Goethe was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, critic, artist; he is considered the greatest German literary figure of the modern era, his high standing in the community, even during his lifetime, simply cannot be overstated.

One day Goethe invited a guest for lunch, he decided not to announce who he was nor tell his daughter-in-law anything about him. During the meal Goethe was relatively quiet, not wanting to disrupt the free speech of his talkative guest, who was said to have elaborated on himself using oddly complicated grammatical forms and obscure terminology, a mode of expressing mentally over-leaping itself, the peculiar philosophical formulations of the animated guest reduced Goethe to complete silence. Later, after the meal was over and the guest had departed, Goethe asked his daughter in law, “Now how did you like the man?” “Strange” she replied, “He did not seem to be a clear thinker, I cannot tell whether he is brilliant or mad.” Goethe laughed ironically, “Well my dear, for your information you have just now dined with the most famous of our modern philosophers, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel”.

Yet, Hegel does have interesting things to say and important things to teach us.

Hegel felt that we should mine history in order to learn from it and that each era, even the unpleasant one’s had something to teach us. Hegel also insisted that we see what may be learned from even those points of view we disagree with or that seem alien to us, we should try to understand these points of view, their origins and what is motivating these decisions and stances and learn from them what we can, even if we detest them. Hegel wanted us to understand that important ideas can come from anywhere.

Hegel understood that societies made progress by lurching from one extreme to the other, overcompensating for previous mistakes; he noted that it generally took three moves or shifts before the right balance was struck on any issue and this is what he called the ‘dialectic’. Beginning with a thesis and then swinging to its antithesis before arrive somewhere back in the middle with a synthesis. It is in this way that we find the new solutions, combining the best elements of each extreme to find the right balance, the right answers for their time.

Look at what is happening in American politics right now, if the outgoing Democratic Presidency of Barak Obama was the thesis, the incoming Presidency of the Republican, Donald Trump is the antithesis, the severe lurch and overcompensation in the opposite direction. In Hegelian Dialectics the next presidency should be a synthesis of the better elements of the two extremes of these governments, a more middle-ground philosophy, be that Democrat or Republican.

Hegel helps us to seek valuable insights where we may not have thought to or may have even resisted looking for them: in art, in institutions and in the mistakes and extreme swings and reactions in our history and in other peoples. For Hegel, growth comes as a result of the clash between divergent ideas.

As previously mentioned, it has recently been somewhat controversially suggested that almost everything we know about Hegel is wrong! Hegel only published two books in his lifetime and much of what we are left with as Hegel’s posthumously published works is taken from lecture notes that have been translated, interpreted, divined and expanded upon firstly by his students and then by a great many scholars and intellectuals and this has been going on ever since Hegel’s untimely death from a cholera outbreak when he was sixty-one years old.

Hegel published the ‘Phenomenology of Mind’, (sometimes translated as the Phenomenology of Spirit) in 1807 and the ‘Science of Logic’ over three volumes in 1812, 1813 and 1816. His work the ‘Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences’ was also published in his lifetime: first in 1817 with a second edition 1827 and a third in 1830. However, the Encyclopaedia was meant to be an accompanying pedagogical aid for those who attended his lectures and not a book in itself.

These were not stand alone books, they are to accompany lectures and interestingly they have tripled in size since they were first published. Because of his sudden death, Hegel did not get to collate, edit and publish the vast tomes of notes and material he had accumulated. His students and followers mined this material and published their works on behalf of Hegel’s remaining family.

So, all these works published after Hegel’s death are not his considered philosophical theories and conclusions, they are works divined by other people based on his notes, thought bubbles and lines of chaotic text meant to accompany lectures. So confusing where much of the results that most people do not bother to read them through and simply read other people’s notes, introductions, thoughts and criticisms of the original works. He has been called the most famous unknown philosopher in the world, cited more often than he is read and discussed far more than he is understood.

There are vast differences between reading Hegel and reading about Hegel, it is just not the same at all. Almost everyone who has heard anything about Hegel knows about his Hegelian dialectic, yet recent critics and scholars contest that this theory just does not exist in Hegel’s work at all and we can know this simply by reading all of Hegel’s actual texts.

Another founding figure of German Idealism, the philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814) is today identified as the initial author of the dialectic. Heinrich Moritz Chalybäus (1796–1862) was a German philosopher best known for his exegetical work on Hegel’s dialectic and positing it as the triad of “thesis–antithesis–synthesis.”

Whether this is contested or not -it will probably forever be known as the Hegelian Dialectic and whilst the phenomenon is not always true- quite often, we can quite easily think of many examples in our lives of a thesis, an antithesis and a synthesis or, a contested system being over-corrected before a middle-ground-consensus is achieved.

How could two extreme, contradictory viewpoints both be true? As John Lonsdale writes in the New York Times; ‘One great thinker on this issue is G.W.F. Hegel: The abstract thinking of the understanding is so far from being something firm and ultimate that it proves itself, on the contrary, to be a constant…overturning into its opposite, whereas the rational as such is rational precisely because it contains both of the opposites as ideal moments within itself.

This is what I mean by a “dialectic”, where the truth exists at different extremes and the actual truth is a complex interaction between an initial understanding and its negation. The idea is that most polarizing viewpoints, whether practical or theoretical, contain within themselves apparent contradictions which seem to drive one to the opposite pole. But much as a Zen master appreciates both sides of a koan, one should strive to recognize that two contradicting extremes can often be simultaneously valid.

Many people are sloppy thinkers and opt for “middle of the road” positions when faced with two opposing extremes. But compromise is often even less accurate than the extreme poles of a dialectic. In my experience, it’s common that deep truths exist at both extremes of a dialectic, and the wisest stance on an issue will incorporate “both of the opposites within itself”.

Deeply understanding something and being a passionate advocate on one side of a debate (even in a way that may make others uncomfortable) is a great start, and the path to wisdom. But with maturity comes the insight that you should remain open to ideas and views totally incompatible with your own. I have learned that if I only see and deeply appreciate one side of an argument it means I am probably missing something important.’

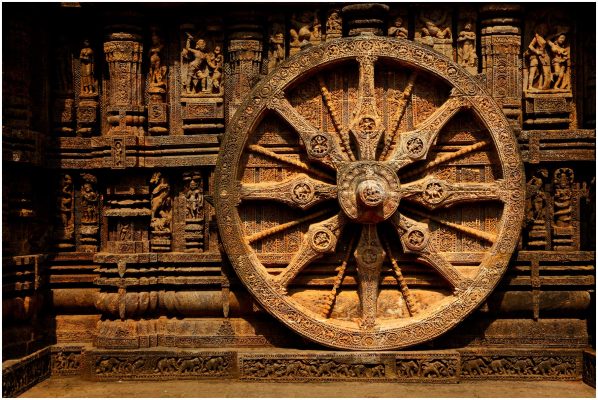

Is it possible that in the recent dramatic swing, (in some markets) towards extreme examples of ‘natural wines’ we are witnessing the severe lurch away from the thesis of wine refineries, global brands and wines made to gold medal winning recipes? And is it not therefore also possible that a synthesis will emerge to again take the industry another turn of the wheel forward?