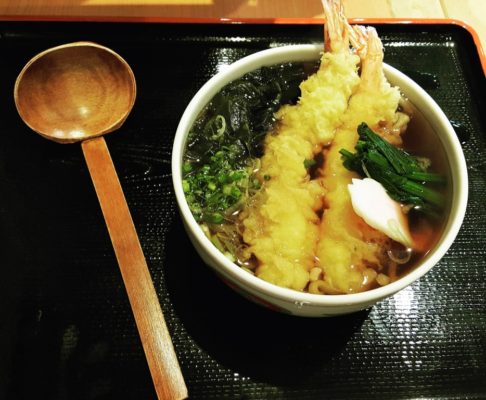

I could be sitting in one of those little hole-in-the-wall noodle bars in the subterranean arteries of the Tokyo Metro subway, instead I am seated in a concrete box that abuts the pavement on Street 334 in Boeung Keng Kang 1, Phnom Penh, Cambodia; a Japanese restaurant not much larger than a shipping container.

As you walk in through the traditional ‘noren’ curtain you enter a concrete cubicle that can squeeze about 16 people in per sitting. There is a small, low shelf set against the wall which supports a glass brief case containing the clichéd display of plastic food, a ‘shokuhin sampuru’ of cold soba noodles topped with flakes of nori; the display looks as though it has been artistically placed for absurdist effect.

Japanese menu-chits are clipped up on the wall along with small packets of plastic children’s toys, candies, trading cards and the cut-out head-shots of two Japanese Spitz pups, (Pomeranians) which nicely complete the sense of ‘kawaii’, the Japanese term for the aesthetic of cuteness and adorability.

The restaurant is known as Soba, Udon, Chiyoda, the latter being a nod to the inner Tokyo ward that houses the Imperial residence, home to the Emperor of Japan. Chiyoda literally translates as “field of a thousand generations” whilst Soba and Udon are some of Japan’s most famous noodles, enjoyed by generations of Japanese families that may also be counted in their thousands. There are many allegories and legends regarding the origins of Soba and Udon noodles however, it is accepted history that they became enormously popular during the Edo period in the early 1600’s, especially through the proliferation of the Yatai, noodle carts.

Soba, Udon, Chiyoda restaurant specializes in producing handmade soba and udon noodles, made fresh up to three times a day by chef Nobuhuko Kado, (Nobu) who spent fourteen years learning the craft of making noodles by hand. A soba noodle master must adjust his dough according to things like air temperature, air moisture, the brand of buckwheat or even the coarseness of the grind; Nobu has been adapting and perfecting his dough to suit the climate of Phnom Penh and (in my opinion) he has reached a level somewhere near perfection. Producing handmade noodles is a Zen like, meditative process that is said to require a communion between the maker, the universe and the dough.

Noodles are hand cut in a very deliberate and meticulous manner using a wooden guide board and a special knife known as a ‘Soba Kiri’, Udon (wheat noodles) and other handmade noodles also have their own special knives. The soba kiri is like a large, meat cleaver like blade that curves back under the handle so that the cutting edge runs the length of the entire knife; it is a rudimentary yet precise instrument.

Kazuo Ishiguro is one of my favourite authors; born in Nagasaki in 1954 he moved with his family to Britain in 1960, where he first grew to become an adult and then became one of the most celebrated writers in the English speaking world. His list of works includes ‘The Remains of the Day’ (1989), ‘When We Were Orphans’ (2000) and ‘Never Let Me Go’ (2005). In ‘When We Where Orphans’ Ishiguro uses sparse language and fading memory to create a vast and murky emotional landscape in a collapsing time and space where readers soon find themselves lost and on unsteady ground. Ishiguro’s characters are often struggling to resolve issues from their past and he likes to leave readers at the end of his stories without any clear resolution, giving them what has been described as a ‘melancholic resignation’. I cite Ishiguro here not because he was born in Japan and is Japanese but, because this feeling he leaves you with at the end of several of his novels is perfectly described in Japanese as ‘Mono no aware’ a term that is said to describe a sensitivity or empathy towards ephemera.

When I am eating Mr. Nobu’s fresh, handmade soba noodles I have a sense of ‘mono no aware’ but I am not talking about the written ephemera of pulp fiction, pamphlets, trading cards or the menu chits stuck up on the wall of his restaurant. Here I am talking about a literal translation: ‘a pathos for transient things’, something I sense growing in me as I read the narrative told to me in a bowl of fresh noodles.

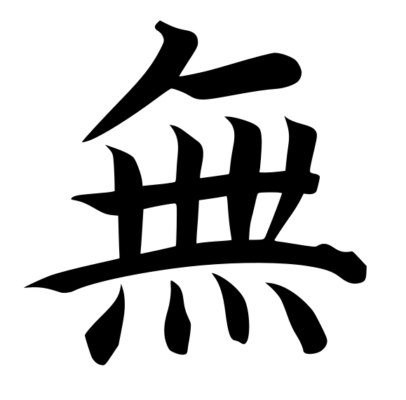

Wabi Sabi is more than a Japanese aesthetic; it is a way of living and a way of viewing the world, it is (to me) profound, it is Zen and it is beauty. Wabi-sabi is the acceptance of transience and imperfection and it is finding the wisdom, peace and beauty within these paradigms which gives rise to a sense of melancholy and a spiritual longing.

Zen and Mahayana philosophy espouse acceptance and contemplation of the imperfection, impermanence and fluctuation of all things and art influenced by such philosophy embodies a wabi-sabi aesthetic, this includes artistic rituals such as the Japanese tea ceremony and (for me) the experience of producing, preparing, serving, slurping and digesting fresh, handmade noodles. In a world being devoured by plastic, where dried, packaged noodles are replacing ‘fresh’ noodles all over the planet, this is a moment of ‘zazen’ a moment of pure culinary bliss.

‘Kintsugi’ is another Japanese wabi-sabi art, it is the art of repairing broken pottery with gold, the philosophy of ‘kintsugi’ is that an object becomes more attractive when repaired because its newly highlighted cracks tell the story of the journey and uniqueness of the object, now made more beautiful by its history, its scars and its imperfections.

As I enjoy my bowl full of steaming broth, the golden soba noodles looking like the cracks and veins of a ‘kintsugi’ bowl, I become aware of its restorative powers, its ability to revive, rejuvenate and give comfort, for here it is I and not the bowl that is being repaired, this is soba for the soul.

Fresh soba is served either cold with a light dipping sauce or hot in a broth where it may come with chicken, mushroom, tempura prawn or other such delicacies. One of my favourites is in a light, warm broth with tempura scraps. Unlike other noodles that have a more neutral flavour, the fresh, nutty, clean flavours of the buckwheat come through in the soba noodle and it can be allowed to shine in the dish.

That is what is so special about fresh, handmade soba, and when the noodles are adjusted specifically for the climate by a master noodle maker, it is what makes soba from this restaurant so special. Here the soba has a delicious texture and an incredible flavour, unmatchable with dried, packet soba.

I have also tried the udon and found its texture stunning and I must also add that the tempura here is some of the very best I have experienced in Cambodia or the region. The menu at Soba and Udon, Chiyoda is relatively small but varied and interesting and there are always specials and added dishes. Prices are extremely reasonable and there is a wide enough range of sakes and Japanese beers.

The small front of house team here is always smiling and happy, they are very friendly and I have quickly found that I just love coming to this place for the food, the ambience, the people and the special overall feeling I get when I eat here.

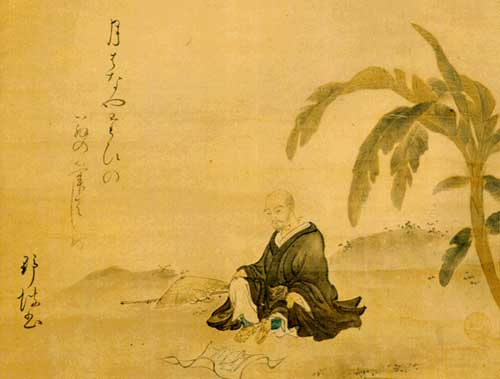

In the Edo period of Japanese history, sometime in the mid sixteen hundreds, Matsuo Basho was a warrior in training having been born to a samurai. After the death of his Shogun Basho left home, giving up all hope of ever becoming a Samurai and instead, devoted his life to Renku and Hokku, (Haiku) poetry.

Basho’s talent was quickly brought to the attention of the masters and he received special teaching, soon Basho himself was teaching and had many devoted students.

A restless soul, Basho practiced Zen mediation to try and ease his disquiet, eventually he decided to set off on the first of what would become known as his four epic journeys. These wanderings were considered to be highly dangerous and Basho himself said that he expected to die in the middle of nowhere or be murdered by bandits.

As Basho wandered his poetry began to change, he began writing about the world around him, the things he could see and the changing seasons, he became less introspective and more in the moment. Soon, Basho’s poetry was spreading out ahead of him and as he traveled, he found friends and followers waiting to meet him wherever he went.

Many of Basho’s Haiku poems include references to the fields of buckwheat, (soba) he encountered on his journeys including his magnum opus, ‘Oku no Hosomichi’, (The Narrow Road to the Deep North) which is considered by many to be his finest achievement.

I’ll serve soba

while they are blossoming,

mountain path

——

Gaze at the soba too

and make them envious,

bush clover in the fields

——

Under the crescent moon

the earth is shrouded in mist,

soba blossoms

As I read Basho’s beautiful haiku, with its ‘kiru’ and its ‘kireji’ I am again reminded of the principles of wabi-sabi and the feelings of ‘Mono no aware’ and the impermanence and constant flux of life. The book ‘Oku no Hosomichi’ describes a journey on foot by Basho which is said to have covered nearly 2,500 kilometres and taken a little over 150 days to complete. After the journey was over Basho spent five years working and reworking the poetry, the book was not released until after he had died.

An epic journey, a labour of love describing the beauty, impermanence, transience and imperfection he saw all around him, distilled down over five years into a work of such simple beauty. Haiku; three phrases, three to seven words per phrase, seventeen ‘on’ or ‘mora’, (like syllables and timbre) per poem, each poem taking mere seconds to read; simple lines that have brought joy and contemplation into the lives of thousands for generations past and generations to come.

Going to restaurants that serve cuisine from different countries, be it Italian food, Chinese food, Thai, Vietnamese, French, Spanish or Japanese is a bit like going on a foreign holiday, an escape into someone else’s culture, a small journey into someone else’s world.

I reflect on the efforts of Mr. Nobu, of his fourteen years learning to make noodles by hand, his journey to Cambodia and his two years perfecting the dough to suit his new home, his precise and methodical kneading and cutting every day and the preparation of his dishes, for me to come for lunch, order a bowl and slurp them down in minutes, before paying my bill, saying my thanks and heading back out into the street.

This is why it is one of life’s simple joys, a thing of enormous beauty and living poetry. A journey, a passion, meticulous work all fused and distilled down into a few humble lines of golden noodles in my bowl, that have the ability to bring a special moment of joy into my day and into my life, just as fresh soba has been doing since the time of Basho.