The Composer

Giacomo Puccini has been called “the greatest composer of Italian opera after Verdi”. While his early work was rooted in traditional late-19th-century romantic Italian opera, he successfully developed his work in the ‘realistic’ verismo style, of which he became one of the leading exponents.

He is the creator of some of the most enduring and often performed operas in history including La Bohme, Tosca, Madam Butterfly and Turandot (unfinished at the time of his death and completed by Franco Alfano based on Puccini’s sketches).

Today, Puccini is by far the most-performed composer among his Italian contemporaries, and the same was true during his lifetime.

“Puccini succeeded in mastering the orchestra as no other Italian had done before him, creating new forms by manipulating structures inherited from the great Italian tradition, loading them with bold harmonic progressions which had little or nothing to do with what was happening then in Italy, though they were in step with the work of French, Austrian and German colleagues.”

Ravenni and Girardi

The Conductor

Arturo Toscanini, (March 25, 1867 – January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed musicians of the late 19th and 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orchestral detail and sonority, and his photographic memory. He was at various times the music director of La Scala Milan, the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. Later in his career he was appointed the first music director of the NBC Symphony Orchestra (1937–54), and this led to his becoming a household name (especially in the United States) through his radio and television broadcasts and many recordings of the operatic and symphonic repertoire.

Toscanini conducted the world premieres of many operas, four of which have become part of the standard operatic repertoire: Pagliacci, La bohème, La fanciulla del West and Turandot; he took an active role in Alfano’s completion of Puccini’s Turandot.

The opera had its world premiere in Turin on the 1st of February 1896 at the Teatro Regio, conducted by Arturo Toscanini. La bohème has become part of the standard Italian opera repertory and is one of the most frequently performed operas worldwide. In 1946, fifty years after the opera’s premiere, Toscanini conducted a performance of it on radio with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, this performance was eventually released on records and on Compact Disc, it is the only recording of a Puccini opera by its original conductor.

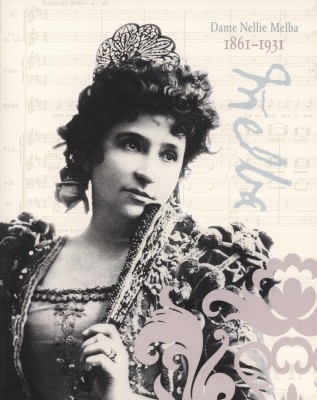

The Diva

The Yarra Valley’s very own opera diva, Dame Nellie Melba, enchanted the world as Mimi in ‘La Boheme’.

Dame Nellie Melba GBE (19 May 1861 – 23 February 1931), was an Australian operatic soprano. She became one of the most famous singers of the late Victorian Era and the early 20th century. She was the first Australian to achieve international recognition as a classical musician.

Born Helen Porter Mitchell she took the name Melba which was a condensed version of her beloved home city of Melbourne. If anyone was a legend in her time it was Dame Nellie Melba. In 1886 she left Australia for London, England and then went on to Paris, France to study with Madame Marchesi who recognized a ‘great angelic quality’ in her voice. Dame Nellie Melba made her debut in Brussels in 1887 to rave reviews and by 1888 had established herself as the prima donna of Covent Garden, a position she held until the mid-1920.

She made her operatic debut as Gilda in Rigoletto at La Monnaie on 12 October 1887. The critic Herman Klein described her Gilda as “an instant triumph of the most emphatic kind … followed … a few nights later with an equal success as Violetta in La Traviata.

The following year, she performed at the Opéra in Paris, in the role of Ophélie in Hamlet; The Times described this as “a brilliant success”, and said, “Madame Melba has a voice of great flexibility … her acting is expressive and striking.”

Melba was persuaded to return to Covent Garden for Roméo et Juliette (June 1889), she later recalled, “I date my success in London quite distinctly from the great night of 15 June 1889.” After this, she returned to Paris as Ophélie, Lucia in Lucia di Lammermoor, Gilda in Rigoletto, Marguerite in Faust, and Juliette. Of this time the composer Delibes said that he did not care whether she sang in French, Italian, German, English or Chinese, as long as she sang.

Melba sang the role of Nedda in Pagliacci at Covent Garden in 1893, soon after its Italian premiere. The composer was present, and said that the role had never been so well played before. In December of that year, Melba sang at the Metropolitan Opera in New York for the first time. Her performance in Roméo et Juliette, later in the season, was a triumph and established her as the leading prima donna of the time.

Even though some of her greatest triumphs occurred elsewhere, most notably at La Scala in 1893 and repeatedly in New York, it was to Covent Garden that Melba returned season after season, maintaining a permanent dressing room to which she alone held the key. There she reigned supreme. In 1913 Covent Garden commemorated the twenty-fifth anniversary of her first appearance there with a gala performance: Melba appeared as Mimi in La Bohème, a role she had studied with the composer and made famous.

Established as a leading star in Britain and America, Melba made her first return visit to Australia in 1902–03 for a concert tour, also touring in New Zealand. The profits were unprecedented; she returned for four more tours during her career. In Britain, Melba campaigned on behalf of Puccini’s La bohème. She had first sung the part of Mimi in 1899, having studied it with the composer. She argued strongly for further productions of the work and was vindicated by the public enthusiasm for the piece, which was bolstered in 1902 when Enrico Caruso joined her in the first of many Covent Garden performances together. She sang Mimi for Oscar Hammerstein I at his opera house in New York, in 1907, giving the enterprise a needed boost.

Although she was entering her forties, Melba was at the peak of her career. She was commanded to sing for the president of France at Buckingham Palace; in 1904 she created the title role in Saint-Saëns’ opera, Helene, at Monte Carlo; and in 1906-07, since she was displeased with the Metropolitan, she deserted it for the recently founded, rival Manhattan Opera House, which she revived financially with a triumphant season. It was probably her finest hour.

A splendid constitution and tenacity of purpose, allied with exceptional powers of concentration and attention to detail, were elements of a charismatic personality which enabled Melba to remain for so long in the forefront of the musical world.

Her sense of theatre comprehended the audience as well as the piece in hand; on one occasion her direct intervention from the stage prevented a panic when fire broke out, and in a production of The Barber of Seville in San Francisco in 1898, the year of the Spanish-American war, she won the hearts of a restless audience by singing ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ in the music-lesson scene.

She was at her best either in those parts which required a light voice, such as Gilda, Lucia, or Marguerite, or which did not require too great an exploration of psychological complexities, such as the lusty Nedda or the pathetic Mimi. She sang with seeming effortlessness, producing a voice which Sarah Bernhardt described as being ‘pure crystal’, and which the soprano Mary Garden admired for the way it left the stage and seemed to hover in the auditorium like a beam of light. For Percy Grainger, ‘Her voice always made me mind-see Australia’s landscapes’.

It was as ‘the Voice’ that Melba sometimes chose to describe herself. ‘Good singing’, she stated, ‘is easy singing’; nature had given her an almost perfect larynx and vocal cords. Her range was fully three octaves, while her registers were so well blended that even an eminent throat specialist thought they were one. A scientific measurement of her trill produced twenty feet of undulations between perfectly parallel lines. Instrumentalists admired her, not least for the way that, despite her imperious temperament, she scrupulously sought to realize the composer’s intentions. From 1904 Melba began recording; she issued over one hundred records and helped to establish the gramophone.

On 15 June 1920, Melba was heard in a pioneering radio broadcast,she was the first artist of international renown to participate in direct radio broadcasts. Radio enthusiasts across the country heard her. Further radio broadcasts would include her Covent Garden farewell performance, and a 1927 “Empire Broadcast” (broadcast throughout the British Empire, by radio stations AWA and 2FC, Sydney, on Monday 5 September 1927; it was relayed by the BBC London on Sunday 4 September).

In 1909, Melba bought property at Coldstream, a small town near Melbourne, and around 1912 she had Coombe Cottage built. She also set up a music school in Richmond, which she later merged into the Melbourne Conservatorium. She was in Australia when the First World War broke out, and she threw herself into fund-raising for war charities, raising £100,000. In recognition of this, she was created a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in March 1918, “for services in organising patriotic work”.

After the war, Melba made a triumphant return to the Royal Opera House, in a performance of La bohème conducted by Beecham, which re-opened the house after four years of closure. The Times wrote, “Probably no season at Covent Garden has ever started with quite the thrill of enthusiasm which passed through the house.”

In 1922 Melba returned to Australia, where she sang at the immensely successful “Concerts for the People” in Melbourne and Sydney, with low ticket prices, attracting 70,000 people. In 1926 she made her farewell appearance at Covent Garden, singing in scenes from Roméo et Juliette Otello, and La bohème. She is well remembered in Australia for her seemingly endless series of “farewell” appearances, including stage performances in the mid-1920s and concerts in Sydney on 7 August 1928, Melbourne on 27 September 1928 and Geelong in November 1928. From this, she is remembered in the vernacular Australian expression “more farewells than Dame Nellie Melba”.

In 1929 she returned for the last time to Europe and then visited Egypt, where she contracted a fever that she never entirely shook off. Her last performance was in London at a charity concert on 10 June 1930. She returned to Australia but died in St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney in 1931, aged 69, of septicaemia. She was given an elaborate funeral from Scots’ Church, Melbourne, which her father had built and where as a teenager she had sung in the choir. The funeral motorcade was over a kilometre long, and her death made front-page headlines in Australia, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Europe. Billboards in many countries said simply “Melba is dead”. Part of the event was filmed for posterity. Melba was buried in the cemetery at Lilydale, near Coldstream. Her headstone bears Mimì’s farewell words: “Addio, senza rancor” (Farewell, without bitterness).

On first-name terms with the great, she would sing at their houses only when it pleased her: a not unreasonable attitude when, in addition to her tours to Continental opera houses, she had been invited to sing in St Petersburg before Tsar Alexander III, had sung in Stockholm before King Oscar II, in Vienna before Emperor Franz Joseph, and in Berlin before Kaiser Wilhelm II; she had also been commanded by Queen Victoria to Windsor. ‘Years of almost monotonous brilliance’ was the summation on her Covent Garden farewell programme. When she appeared in distant places, she was mobbed (much as pop-singers are today). Meanwhile friendly advice from Alfred de Rothschild strengthened her financial position. Her autobiography shows that Melba’s social successes were quite as important to her as her singing ones. Yet, as she once remarked to an inquiring aristocrat, ‘there are lots of duchesses but only one Melba’.

For years her portrait has hung in the famous La Scala opera house in Italy’s city of Milan.

She sang the famous role of Lucia at La Scala in 1893.

Melba toast is a very dry, crisp, thinly sliced toast often served with soups and salads or topped with either melted cheese or paté named after Dame Nellie Melba. Melba toast was created for her by chef Auguste Escoffier in 1897, when she was very ill and this kind of toast became a staple of her diet.

The Peach Melba is a classic dessert invented in 1892 or 1893 by Auguste Escoffier at the Savoy Hotel, London to honour Dame Nellie Melba. It combines two favourite summer fruits: peaches and raspberry sauce accompanying vanilla ice cream.

He had heard Nellie Melba perform at Covent Garden one night and was inspired to create a dessert just for her. Rumour had it she loved ice cream, but did not dare eat it often, believing it would affect her vocal cords. Escoffier created a sauce of raspberries, redcurrant jelly, sugar and cornstarch. In Peach Melba, the ice cream, being only one element in a whole, would not be as cold and thus not harm her vocal cords. He served it at a dinner she was hosting, presented in an ice sculpture of a swan inspired by the performance of Lohengrin he had seen.

Dame Nellie Melba appears on the Australian $100 note.

Melba was closely associated with the Melbourne Conservatorium, and this institution was renamed to the Melba Memorial Conservatorium of Music in her honour in 1956.

The music hall at the University of Melbourne is known as Melba hall.

The suburb Melba in Australian Capital Territory and the Melba Highway in Victoria’s Central Highlands were named after her.