Master Meng

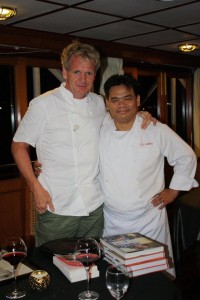

Internationally, Luu Meng is Cambodia’s most recognizable chef and is regularly visited by global celebrity chefs such as Gordon Ramsay and Anthony Bourdaine. Locally, he has earned the respect and admiration of his peers; he is president of the Cambodia Hotel Association, sits on the board of the Cambodia Restaurant Association and is co-author with Clive Graham-Ranger of the book ‘Cambodia’s Top Tables’. He has prepared meals for his King, Prime Minister, countless international dignitaries, movie stars and business moguls and is regularly invited -along with the Cambodian Ministry of Tourism- to promote Khmer cuisine around the globe.

Meng is a smart businessman and a creative entrepreneur, whilst he remains humble, he is always an available public face for the media if he can see a way of getting his message across; the message is that Cambodian cuisine is ready to join the pantheon of the world’s great international cuisines.

“It deserves a place at the same table as French, Italian, Chinese and Thai haute cuisine”, he states with typically tempered determination. “This is my passion and my future,” he admits. “I am constantly looking at and tasting traditional dishes with a view to making minor alterations to improve or modify their taste for the modern palate.”

Recently, the French ambassador in Cambodia awarded the chef with the Order National de Merite Agricole (the National Order of Agricultural Merit) for ‘his creation of Cambodian nouvelle cuisine and building a bridge to other culinary cultures’.

In the form of a prestigious medal, the order of merit was established in France on July 7, 1883, by Jules Meline, to reward services to agriculture.

As an indication of the order of merit’s significance, Luu Meng joins such historical luminaries and culinary greats as microbiologist, Louis Pasteur, pioneering chef, Elizabeth David, Rene Renou, one of the most influential figures in French winemaking, and Jacques Chirac, the former French president.

After the ceremony at the French embassy, Luu Meng reflected that: “As a simple boy from Cambodia whose mother ran a sidewalk café in Phnom Penh, I am deeply moved that the French government should honour me in this way, particularly as such recognition is for pursuing my passion and my love of food.”

An inspiring performance from the man whose father came to Cambodia fleeing Mao Zedong’s long march only then to have to endure the time of the Khmer Rouge. The family survived this horror by following his grandfather’s advice to ‘stay by the water’, always sticking close to the river’s edge until reaching the refugee camps on the Thai border.

“I come from a family of chefs. My grandmother was a chef and my mother had a restaurant in Phnom Penh, we always had good food at home. Then, when I was three years old, we were forced to move to a border refugee camp which was under U.N. control. Whilst there, I learnt English and returned to Phnom Penh when I was 18 years old to study further. At this stage, I knew I wanted to be a chef, so I travelled to Thailand to study at a hotel school, and later gained experience in other countries, including Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam”.

In 1993 Meng began cooking at the Hotel Cambodiana and within two years had risen to the position of Sous-Chef. It was here that Meng first met his future business partner Arnaud Darc, then working in the hotel’s finance and purchasing departments; it was also the time when his idea of reviving and refining Khmer cuisine was born, an idea that would eventually give birth to Cambodia’s first and most famous renaissance restaurant, Malis.

Malis would propel Meng onto the international culinary radar, it is his temple of ‘living Cambodian cuisine’ as he calls it, for the kingdom of Cambodia it is a beacon on the international culinary map.

Khmer cuisine is one of the world’s oldest living cuisines and one of the most resilient on the planet. When asked to describe Khmer cuisine Meng explains, “Cambodian cuisine was very famous around 1965, but the creativity stopped because of the war. Then, we came up with some ideas to rejuvenate traditional flavours, and also fuse it with other influences. I wanted to not only recreate Khmer cuisine I wanted to create a living food culture, a Khmer cuisine that was relevant to today and progressive, with an eye to the future.”

When asked how it differentiates itself from the cuisine of its neighbours Meng notes, “Thai food is hot, spicy and sweet, while Vietnamese is more Chinese influenced, Khmer cuisine is all about fresh spices. There are influences from India, but always with fresh ingredients, not powders. Our cuisine is not as spicy as Thai and we don’t use as much fish sauce as Vietnam, although we do love our prahoc [fish paste].” He pauses to reflect, “It’s all about the freshness.”

Today, you could be excused for thinking that it was time for Meng to start basking in the glory of International recognition, purchase a few sports cars and spend long breaks at a country estate however; you would be completely off the mark.

Far from succumbing to the trappings of celebrity, Luu Meng is all about simply getting on with it, from educating people about Cambodian cooking both at home and abroad, to paying strict attention to detail in the kitchen; all the while remaining emphatically passionate about pushing the gastronomic boundaries in his own pursuit of culinary excellence.

He is also all about providing for his family, building strong businesses and creating career paths for young Cambodians. Meng launched the upscale, boutique Almond Hotel, which houses the Yi Sang Cantonese Restaurant on its ground floor on Sothearos Boulevard, soon followed by a chain of Yi Sang restaurants strategically positioned throughout Phnom Penh.

With business partner Arnaud Darc, Meng is also a partner in Topaz, one of Phnom Penh’s most respected French fine dining restaurants. There are also newer additions to the Meng corporate empire, Feeling Home serviced apartments, Secret Recipe outlets and no doubt there will be even more to come from this ambitious and self-confessed workaholic.

Yet it is for his inspirational work to restore a nation’s cuisine and make it relevant to modern diners and for his unswerving determination to lift the standards of his industry and promote his country’s culinary credentials that has made him a national hero. For all his outstanding achievements to date, Meng remains humble, keeping it simple and approaching his passion with honesty and integrity, (he will be horrified to see me describing him as a national hero and probably take me to task for it next time we meet).

I don’t recall a single conversation with Meng (and we have many), that did not either begin or end with the topics of promoting Cambodian cuisine, produce, agriculture or, with him dissecting a traditional or new culinary philosophy. In a recent magazine interview that we happened to be doing together, I recall Meng stating that some local chefs are taught to cook by numbers, for them it is all about cooking on a production line, cooking to costs and returns but, this was no good according the master, “You have to love the food, if you love the food then you love what you do, this is the most important thing”, he stated emphatically.

Whenever I bring new wines into Cambodia I immediately arrange a food and wine matching session with Meng, for both of us to learn how the wines might best work with Cambodian cuisine.

Meng is living Cambodian culture when it comes to gastronomy, what he leaves behind will be just as important as the food he is creating now and right now, the food empire he is creating is very important to Cambodia indeed.

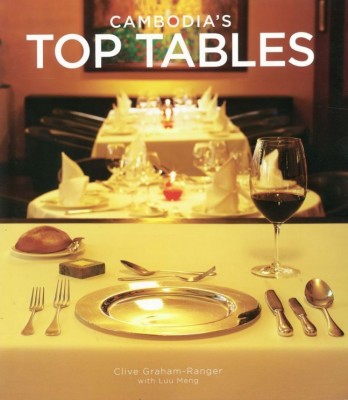

Meng, along with our stalwart friend Clive Graham-Ranger, has just completed a book that I was also fortunate to have been a small part of, ‘Cambodia’s Top Tables’ celebrating our selection of the nation’s best restaurants and its culinary diversity however, it is the next book that I wish my friend to be involved in that I feel is far more important. Much of Cambodia’s culinary tradition was lost during the dreadful period in recent history that locals refer to as ‘Khmer Rouge Time’, beyond that, what remains was passed on as an oral tradition and there is little record of the rapid evolution of both traditional and contemporary Cambodian cuisine. Luu Meng is at the very forefront of that restoration and evolution and I desperately want him to go on record with his recipes, techniques, theories and the places he sources his local produce. I want him to leave a record of his work as a legacy and a resource to teach and inspire future generations of Cambodian chefs and he knows I feel this is very important.

Meng himself is happy to indulge me, he is happy to do it as long as I can convince him it is all about the food and not about the man but, he is still relatively young and has so much going on that I get the sense he feels the time for such things is still some years down the journey.

I am often in awe of his energy, time management, the hours he puts in and his amazing capacity to take on and push through project after project all simultaneously, yet always, instinctively pausing and getting back to basics, in the kitchen at Malis, working with his team, ever striving, refining and defining his ‘Living Cambodian Cuisine’.